Saturday, August 26, 12023 Human Era (HE)

- Continuation Explanation

- Methods of Metabolism

- Three Stages to ATP

- Stage One. Digestion: When to Break and Brake

- Stage Two. Enter the Cytosol

- Stage Three. All Roads Lead to Mitochondria

- At the Centre of Metabolism: A Conclusion of Sorts

- Three Stages to ATP

- How To Train

Continuation Explanation

This post is a continuation of a series on energy and its relationship to stand up paddleboaring (SUP). The impetus for the post came after a conversation with a client on energy systems. We got into some fairly intricate details, and I realized that a refresher for myself was in order. I found that writing a few posts on anatomy and biomechanics specific to SUP served as a great review of my anatomical knowledge, and I thought it would be a fun exercise to refresh on some energy metabolism physiology.

The first instalment covered some background basics before branching into a rant on the semantics of sex-typing, and it ended by attempting to define what energy is. The second instalment looked at work, enthalpy and free energy, and carbon (C) as the building block of life. The third instalment focused on photosynthesis, chemical bonds, and the semantics of systems and states. Instalment four covered adenosine triphosphate (ATP), macronutrients and their utilization and storage, and the mystery of where fat goes when you lose weight. This post continues on, covering the methods of metabolism (i.e., the three stages of ATP production), anaerobic versus aerobic pathways, the old myth of lactic acid and the new truth about lactate, and the end-products of metabolism.

Methods of Metabolism

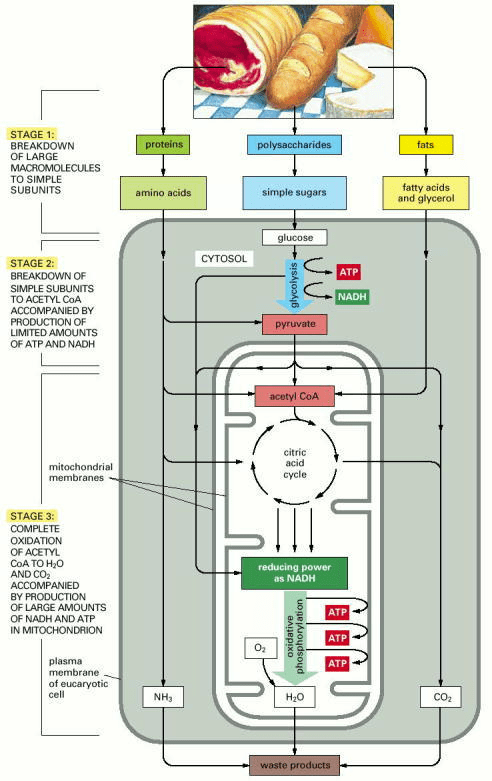

The proteins, lipids, and polysaccharides that make up the food we eat must be broken down into smaller molecules to provide our cells with energy and the building blocks for other molecules. This is done in a step-wise fashion so that the cells can more readily overcome the activation energies while simultaneously allowing more of the free energy liberated to be captured for useful work (see the difference between [A] and [B] below).

Source: Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, et al. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4th edition. New York: Garland Science; 2002. How Cells Obtain Energy from Food. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK26882/

Three Stages to ATP

Source: Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, et al. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4th edition. New York: Garland Science; 2002. How Cells Obtain Energy from Food. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK26882/

Stage One. Digestion: When to Break and Brake

As we saw in the fourth post, we are what we eat. This introduces a problem. The breakdown or catabolism of food must act on the macromolecules taken in from the outside but not take out the macromolecules inside our own cells. The solution to this is that stage one, digestion, occurs outside of the body or cell.

If you take a transverse cross-section (i.e., a horizontal slice) of your body and look at it as a two-dimensional structure, you are an ellipse of stuff with a hole in the middle (at least sort of… for a more in-depth account, check out the video below). That hole is your gastrointestinal tract, so you ultimately have an outer outside (the integumentary system) and an inner outside (the mucosa of the gastrointestinal tract). In three dimensions, this means you are like a twisted tube or donut. One hole in your mouth is connected to the same hole in your anus. The question arises as to whether that even is a second hole (see video)‽ Maybe it is the same hole or perhaps a series of infinite holes‽ Queue the internet debate on “How many holes are there in a drinking straw?” (If you are sure about your answer, pause and consider how many holes are in a pair of pants? One, two, three, or infinite are all arguably correct in my mind, depending on your semantics).

Anyway you slice it, the argument can still be made that what is in your insides, i.e., your digestive tract, is actually on your outsides. Cellularly speaking, the mechanical and enzymatic breakdown of food during digestion is mostly extracellular. Even within cells a sort of extracellular intracellular compartment, the lysosome evolved to evade this problem. Stage one, digestion, breaks the big stuff into little stuff, getting it ready for stage two, where the little stuff gets broken down further inside the cytosol of the cell.

Stage Two. Enter the Cytosol

In stage two, a chain of reactions called glycolysis (Greek for “sweet rupture” from glukus and lusis) converts each molecule of glucose into two smaller molecules of pyruvate. At least, that was the traditional metabolic view. More recent analysis suggests that the end point of glycolysis is actually lactate and not pyruvate, irrespective of oxygen availability. The current view is that glycolysis is neither “aerobic” nor “anaerobic” with respect to oxygen availability because lactate is the obligatory product of glycolysis. Glycolysis is only “anaerobic” in the sense that oxygen is not required for the pathway to operate.

Lactate and pyruvate are chemically very similar. The difference is lactate lacks two additional hydrogens (the respective molecular formulae are lactate, C3H5O3– and pyruvate, C3H3O3–). In any case, glycolysis is likely an ancient metabolic pathway since it can occur in the absence of molecular oxygen (O2, but this is not necessary). It is believed that the anaerobic glycolytic pathway developed prior to cyanobacteria spewing out large amounts of O2 into the atmosphere some 2.4 billion years ago (i.e., the Great Oxidation Event). The fantastic feat of glycolysis is a phenomenal example of how biology figured out how enzymes coupled oxidation to energy storage.

Glycolysis involves a sequence of 10 separate reactions, each producing a different sugar intermediate and catalyzed by a different enzyme. Despite the lack of molecular oxygen involved in glycolysis, it is an oxidation reaction (the term oxidation was first used by Antoine Lavoisier around 11785 HE to signify the reaction of a substance with oxygen, hence the “oxide” root. It was only later realized that the substance, upon being oxidized, loses electrons, thus the term was extended to include other reactions where electrons are lost, regardless of whether oxygen was involved). Electrons are removed by nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) from some of the carbons derived from the glucose molecule, producing NADH (the reduced form). The main function of NAD is the shuttling of electrons to the electron-transport chain in aerobic organisms. If O2 is unavailable to accept the electrons at the end of this process, the system breaks down. So, in aerobic organisms, all metabolic paths eventually lead to carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O). But that brings us beyond just glycolysis, so let us backtrack for a summary.

A simple summary of glycolysis is that a six-carbon atom molecule of glucose is converted into two three-carbon atom molecules of pyruvate (cough, or lactate). For each molecule of glucose, two molecules of ATP are hydrolyzed to provide energy to drive the early steps, but four molecules of ATP are produced in the later steps. At the end of glycolysis, there is consequently a net gain of two molecules of ATP for each glucose molecule broken down (see schematic below).

Source: Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, et al. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4th edition. New York: Garland Science; 2002. How Cells Obtain Energy from Food. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK26882/

Note the two molecules of NADH formed in the glycolysis of one molecule of glucose above. In aerobic organisms, when sufficient O2 is available, these NADH molecules donate their electrons to the electron-transport chain. However, if O2 levels cannot meet the metabolic flux, NADH can not [sic] shuttle its electrons to the electron-transport chain.

Anaerobic Versus Aerobic Glycolysis: Distinction without Difference?

In the majority of animal and plant cells, glycolysis is only the precursor to stage three, the final act in the catabolism of foodstuff. Lactate produced post-glycolysis is portaged to the powerhouse of energy production (well, technically energy conversion, but I was on a roll with P’s), the mitochondria (more on mitochondria below). Inside the mitochondria, lactate is converted to pyruvate by mitochondrial lactate dehydrogenase, which in turn is converted into CO2 plus acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) via another enzyme, pyruvate dehydrogenase. The latter, acetyl-CoA, is subsequently completely oxidized to produce CO2 and H2O through the infamous tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA cycle, a.k.a. citric acid cycle or Krebs cycle) .

Fermentation. It’s Not Just for Beer and Bread.

Anaerobic organisms can grow and divide in the absence of molecular oxygen. For them, glycolysis is the principal source of the cell’s ATP production. Without O2, humans die! However, certain animal tissues, such as skeletal muscle, can continue functioning when molecular oxygen is limited. Though at some point, an oxygen debt (now known as excess post-exercise oxygen consumption or EPOC) must be paid to balance the scales and return the body (or organism) to homeostasis after significant anaerobic metabolism or fermentation. In biochemistry, fermentation is specifically defined as the extraction of energy from carbohydrates in the absence of O2 (so anaerobic metabolism in humans sort of meets that definition since there is not enough O2).

Under anaerobic conditions, the lactate (pyruvate) and the electrons bound to NADH stay in the cytosol rather than entering the mitochondria. Lactate (pyruvate) is converted into products excreted from the cell, for example, ethanol and CO2 in the yeasts used in brewing and breadmaking. In human muscle, what was once thought to be pyruvate as the end-product of glycolysis, which would then be converted to lactate, is now believed to go directly to lactate. This new view means that the “regeneration” of NAD+ from NADH depicted below is a constant process within the cytosol. This availability of NAD+ is required to maintain the reactions of glycolysis.

Source: Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, et al. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4th edition. New York: Garland Science; 2002. How Cells Obtain Energy from Food. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK26882/

Lactic Acid Does Not Cause Fatigue. (Eye Twitch).

A long time ago, in 12008 HE, I completed my Master’s thesis, “The effect of recovery strategies on high-intensity exercise performance and lactate clearance.” Not my first choice of title, it was my advisor’s. As anyone who has completed a thesis or similar project can attest, the topics tend to become a love-hate obsession. For me, the topic of lactate, more commonly, though perhaps erroneously referred to as “lactic acid,” and the belief that it causes fatigue, became and still is a pet peeve of mine. During my undergraduate degree in Human Kinetics, this was the disseminated dogmatic doctrine. During high-intensity exercise, anaerobic glycolysis ends in the production of lactic acid, which results in fatigue. I am not sure if the professors who presented this information knew it to be inaccurate and used the simplification as a pedagogic heuristic, whether they were duped in the dogma themselves, or if somewhere along the way we as students fooled ourselves. Regardless, as I delved into my research topic, I was dismayed to discover the dogma of my academic discipline and the discrepancy between my undergraduate degree and graduate dissertation.

In the literature I consulted, common knowledge was coming to the conclusion that lactic acid, first off, could not exist in the body, and second, it was not the cause of muscular fatigue. In fact, the production of lactate (the form that actually exists in the body) is actually buffering (i.e., acid or proton consuming), preventing the ill effects of metabolic acidosis. Unfortunately, for the curious reader, the cause of muscular fatigue still remains elusive, though it is likely multifactorial and context dependent. I nearly went back to the drawing board to rework my thesis, but at the persuasion of my supervisor, I persisted with my proposed project.

Lactate vs. Lactic Acid

Lactic acid is an organic acid, and lactate is its conjugate base (also known as the lactate anion). An acid, in the Brønsted–Lowry theory, is a molecule or ion capable of donating a proton (i.e., hydrogen ion, H+). There are other theories of acid/base chemistry, but we will go with the Brønsted–Lowry definition. So lactic acid has a proton to donate, whereas lactate as the conjugate base can accept a proton.

Another pertinent point on pungency is the “potential of hydrogen” or pH. The potential of hydrogen is a scale used to specify the acidity or alkalinity of an aqueous solution. Acidic solutions (solutions with higher concentrations of hydrogen ions) are measured to have lower pH values than basic or alkaline solutions. A key concept about pH is that the scale is for an aqueous solution (i.e., in water). The protons that create acid in water are nowhere and everywhere at the same time. At the molecular level, water molecules (H2O) are constantly creating bonds with protons surrounding them to form hydronium (H3O+). Think of it like an intermolecular dance or game of hot potato, with protons being passed around at super speed. Lactate as a conjugate base plays this game, helping to pass hydrogen ions around in the aqueous environment of the body.

Lactic Acid Does not Exist in the Human Body. Or Does it?

Perhaps the biggest problem with blaming high-intensity exercise fatigue on lactic acid is that lactic acid does not really exist in the human body. Or does it? It may be a bit of a semantical issue as to what constitutes lactic acid versus its dissociated form, lactate. Robergs and colleagues (2018) argue that “there is no such entity as lactic acid in any living cell or physiological system.” The true nuance of this argument is above my pay grade. My take is that if lactic acid exists in the body, it does not last at any discernible concentration or for any significant amount of time. This is because the acid dissociation constant (pKa) of lactic acid is 3.86. Since the normal cytosolic pH in a human cell ranges between 7.0-7.4, or in skeletal muscle from approximately 6.7-7.0, any lactic acid produced instantaneously dissociates into the lactate anion and hydronium. For more details on this topic and other relevant misunderstandings about lactic acid in more lay-person language, check out this episode of Fast Talk Laboratories, “Myth Busters—Why We Can’t Talk About Lactic Acid.”

And if you have packed your pocket protector and pince-nez and want to take it up to an extra level of nerdiness, check out this episode of Peter Attia‘s The Drive with Iñigo San Millán, “#85 – Iñigo San Millán, Ph.D.: Zone 2 Training and Metabolic Health,” that does a deep dive into metabolic pathways and their implications for health.

Lactate Production Consumes Protons

Contrary to popular conception, the production of lactate during glycolysis is buffering. That is, lactate production reduces the acidity of the aqueous environment by consuming hydrogen ions, not releasing them. Thus, contrary to popular outdated exercise lore, lactate production (or more commonly mislabelled lactic acid), does not result in acidosis, it retards it. By producing lactate, cells prevent acidosis, staving off the potentially detrimental effects of decreased intracellular pH on metabolism.

Lactate No Longer a Dead-End Product of Glycolysis

Concomitantly, lactate used to be seen as a dead-end product of oxygen-limited (anaerobic) metabolism. It is now known that lactate is produced in fully oxygenated (aerobic) conditions and plays a key role in a myriad of cellular processes. The discovery of lactate shuttle systems demonstrates that lactate is moved between producer (driver) and consumer cells for at least three main purposes; lactate is (1) a major energy source, (2) the major gluconeogenic precursor, and (3) a signalling molecule. During exercise, lactate is cleared predominantly by the liver via gluconeogenesis (i.e., the Cori cycle) and ATP production (i.e., oxidative phosphorylation via the TCA cycle) in the heart and red skeletal muscle. The hepatic uptake of lactate can increase by more than 10-fold during exercise. Cardiac myocytes also take up and oxidize lactate as fuel contributing to 10-15% of cardiac energy provision at rest and approximately 30% during moderate-intensity exercise.

Lactate, via the lactate shuttle, plays a key role in bridging the gap between glycolytic and oxidative metabolism.

Source: Source: Brooks, George A. The tortuous path of lactate shuttle discovery: From cinders and boards to the lab and ICU, Journal of Sport and Health Science, Volume 9, Issue 5, 2020. 446-460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2020.02.006.

Another Shuttle System: Bridging Intracellular Divides

Just like lactate plays a role in bridging the gap between glycolytic and oxidative metabolism via lactate shuttles, another energy shuttle is the phosphocreatine (PCr) shuttle system. It seems ATP has trouble moving about inside the cell. Specifically, most ATP is produced within the mitochondria, a membrane-bound organelle within the cell, and can not easily pass from the mitochondria to the cytosol. The PCr shuttle bypasses this barrier by transferring high-energy phosphate from ATP produced in the mitochondria to the cytosol. Adenosine triphosphate formed via oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondria (see “Stage Three. All Roads Lead to Mitochondria” below) transfers a phosphate to creatine (Cr), via the action of the mitochondrial isoform of creatine kinase (CK), thus generating PCr and adenosine diphosphate (ADP). Phosphocreatine then diffuses into the cytoplasm, where cytosolic isoforms of CK regenerate ATP and Cr. Cytosolic ATP is then available for the ATPases to hydrolyze the molecule for cellular work, and Cr can return to the interior of the mitochondria. The PCr system is the quickest known form of ATP regeneration in the body (see image below).

Source: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4898252/

However, at the expense of speed, the energy available from the PCr shuttle system is limited. Often, the PCr shuttle system is referenced in combination with free intracellular ATP in the cytosol as the phosphagen system. The free intracellular ATP store is extremely limited, estimated to only allow for less than two seconds of maximal effort but can constantly be replenished. Together with the PCr shuttle system, the phosphagen system is estimated to deplete in less than 10 seconds during maximal exertion activity. It is extremely important in explosive-type efforts such as throwing, hitting, jumping, and sprinting.

Just as the phosphagen system can dashingly deplete, it can rapidly replenish during recovery, too. It requires about 30 seconds to replenish approximately 70% capacity and 3 to 5 minutes to replenish 100%. Thus, during intermittent work or intervals (i.e., short periods of activity followed by rest periods), much of the phosphagen system can be replenished during recovery.

Supplementation Speculation

Generally, phosphocreatine store regeneration has been evaluated post-high-intensity exercise. And much of the literature on the subject seems to suggest that phosphocreatine stores are only replenished post-activity during rest. To me, this seems improbable given how the various other metabolic pathways fluctuate depending on local conditions. It seems more likely that phosphocreatine stores replete to some degree during low-intensity exercise, albeit at slower rates for higher efforts. It seems this is now more commonly mentioned in the literature. And, more recently there seems to be more inquiry into the role that phosphocreatine can play in endurance activities.

Metabolic Metaphors: A Gear System

The various metabolic pathways are activated and utilized distinctively depending on the energy demand (i.e., rate and amount) and deplete differentially. Often, the pathways are presented, appearing as a series of events in traditional texts (see image here). In this view, depending on the duration and intensity, the energy pathways appear to be activated sequentially, although there is overlap between temporally adjacent systems. This is an oversimplification, and the image creates an implicit assumption error, particularly that the phosphagen system is fully depleted within the first few seconds of maximal intensity exercise and no longer contributes to energy metabolism thereafter. While, in theory this may be the case during maximal exercise intensity, in practice, it is unlikely that maximal intensity is achieved in most exercise settings.

A parallel pictographic presumption problem presents with the primate progression of past primers. Historically, popular science texts tended to depict human evolution in a way that suggests a similar sequential progression. In the image below, as is the case in other depictions of human evolution, the linear layout gives way to the assumption of a linear process. We now know that this depiction is inaccurate.

As per this episode of The BBC‘s The Infinite Monkey Cage, “The Human Story: how we got here and why we survived,” I am not alone in jumping to the assumption of a linear process of human evolution toward Homo Sapiens. Our current science suggests it was much more of a parallel process with multiple lineages in simultaneous existence. In a similar style, the sequential schematic of energy pathways promotes a simplistic presumption of a non-parallel process.

Metabolic Metaphoric Misrepresentations

As per the iconic human evolution image, the sequential schematic of energy systems, like the one below, can lead to false assumptions.

Source: https://www.thesustainabletrainingmethod.com/

A better depiction is seen in the image below, an excerpt from The Essentials of Obstacle Race Training by David Magida and Melissa Rodriguez from the Human Kinetics blog. The schematic highlights how all energy systems are active for varying intensities and durations of physical exertion but to differing degrees.

Source: https://canada.humankinetics.com/blogs/excerpt/energy-systems

The image above is much more in line with what we know from exercise science. As mentioned, lactate is continuously produced even in fully aerobic conditions. In the graphical schematic above, the glycolytic component of the graph is depicted as overlapping and fully spanning the spectrum of chronological continuity. It is worth noting that an underlying assumption of the schematic is that effort is maximal or near maximal given the high initial flux and early depletion of the phosphagen system. It appears the intensity diminishes with activity duration as indicated by the lower power outputs to the right of the graph. However, I still contend that the image is physiologically inaccurate and leads to false assumptions about metabolic energy pathways.

For example, consider a longer-duration race in which you would need to sprint off of the start line (the marathon in the pictographic schematic). If you started at an intensity that depleted your phosphagen system initially (an “if” I don’t even consider to be possible in a long-duration activity scenario), the depletion would not be maximal, since your body has self-preservation mechanisms that generally do not allow you to exert yourself to such extremes. As your intensity/pace reduced over time, the PCr system would start to replenish in the background as other energy pathways became more predominant. This is not evident in the graphical image since “ATP” and “CP” are shown to diminish to full exhaustion at around 6-10 seconds. Conversely, the pictographic schematic shows that in the “marathon” example, “PCr” and “glycolysis” cumulatively account for an estimated 10% of energy metabolism.

In my opinion, a more accurate depiction in the graphical schematic should show the phosphagen system never fully depleting and operating at a low level throughout the activity duration (or demonstrating an oscillatory wave, though that might have more to do with human inability to truly maintain an exercise intensity steady state). During physical exertion, not all of your cells are under the same metabolic demand. The combination of the circulatory and shuttle systems (e.g., the cell-to-cell lactate shuttle) allows for fuel sources and by-products to be moved throughout the body.

Copied Correctly with Cogwheels

A better conceptualization of the energy systems is to imagine them working in parallel. Any given pathway has the capacity to increase or decrease flux depending on local and systemic factors driving metabolism but is ultimately bound by these factors along with their biological limits. Inevitably, all systems are dependent on the oxidative pathways as O2 must be present, eventually, to keep the system running in animals.

A gear system with multiple cogs running together used to come to mind when I queried this quandary quondamly. Different-sized gears can signal the capacity and speed of the specific system. Giving it more thought now, the gears would need to change size to account for changing metabolic conditions. If anything, perhaps being parallel is most pertinent as a proxy to preserve perspective when pondering the paradigmatic pace-to-power plot.

The image below is a bit over the top with the never-ending cogwheel fractal. But I liked it, and it gets the point across of a continual flux. Here is a link to a more tame version of a planetary gear system that has five turning gears. It is by no means perfect, but in the link, ATP production could be the central orange gear that the other gears are centred around. The three green gears can stand in for free ATP, PCr, and glycolysis. The outer gear would be oxidative phosphorylation as the ultimate end metabolic pathway. But before we tackle oxidate phosphorylation, a few last words on gears.

Getting into Gears Again

Listening to an episode of the Huberman Lab, “Guest Series | Dr. Andy Galpin: How to Build Physical Endurance & Lose Fat,” I was introduced to another great gearing analogy. Dr. Galpin used the example of a bicycle drivetrain to explain the energy systems. I thought this was an excellent analogy since the different sprockets can represent different energy pathways, but the interdependency of the entire system is explicit. I envision the front crankset as the oxidative (aerobic) system. The rear cogset and jockey wheels are the glycolytic and phosphagen (anaerobic) systems, respectively. Most importantly, as is the case in the human body, the anaerobic (glycolytic and phosphagen) and aerobic (oxidative) metabolic pathways are interdependent. You cannot turn the rear cogset without the front crankset turning simultaneously.

Sources: https://www.geardrivetech.com/

https://www.bikelockwiki.com/parts-of-a-bike-diagram/

Dr. Galpin also made reference to the “Breathing Gear System” from Brian MacKenzie. The system serves as a simple way to gauge and scale activity intensity by monitoring respiratory parameters (I will discuss this more in a later post). Essentially, it creates a simple intensity division between oxidative and glycolytic dominant metabolism by distinction of the capacity to breathe nasally versus orally, respectively. It is an easy practical alternative to determining ventilatory thresholds to scale exercise intensity compared to laboratory-based methods. Keep in mind that the assessment of ventilatory thresholds is an attempt to determine what is happening inside the body metabolically.

Stage Three. All Roads Lead to Mitochondria

As the saying goes, ‘All roads lead to Rome.’ With respect to human metabolism, all pathways lead to aerobic metabolism and ultimately the mitochondria. From a geological time perspective, aerobic mitochondrial metabolism is a recent evolutionary road since the Earth’s atmosphere only became oxygen-rich after the Great Oxygenation Event, roughly 2.5 billion years ago. The third oxidative stage of molecular food breakdown takes place within the mitochondria. But where did this odd oblong organelle originate from?

Mysteriously Originating Mitochondria

The endosymbiotic hypothesis of mitochondria’s origin posits that mitochondria arose through a fateful endosymbiosis more than 1.45 billion years ago. Somehow, some time ago, a host cell (either eukaryote or prokaryote) engulfed another cell, the mitochondria, and set the stage for a symbiotic relationship. Essentially, mitochondria are cells within a cell. Mitochondria have their own subset of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) called mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). Mitochondrial DNA in humans (and most multicellular organisms) tends to be maternally inherited. Thanks, Mom! This fact has given rise to the concept of ‘mitochondrial Eve,’ the most recent female human from which all living humans can trace their ancestry.

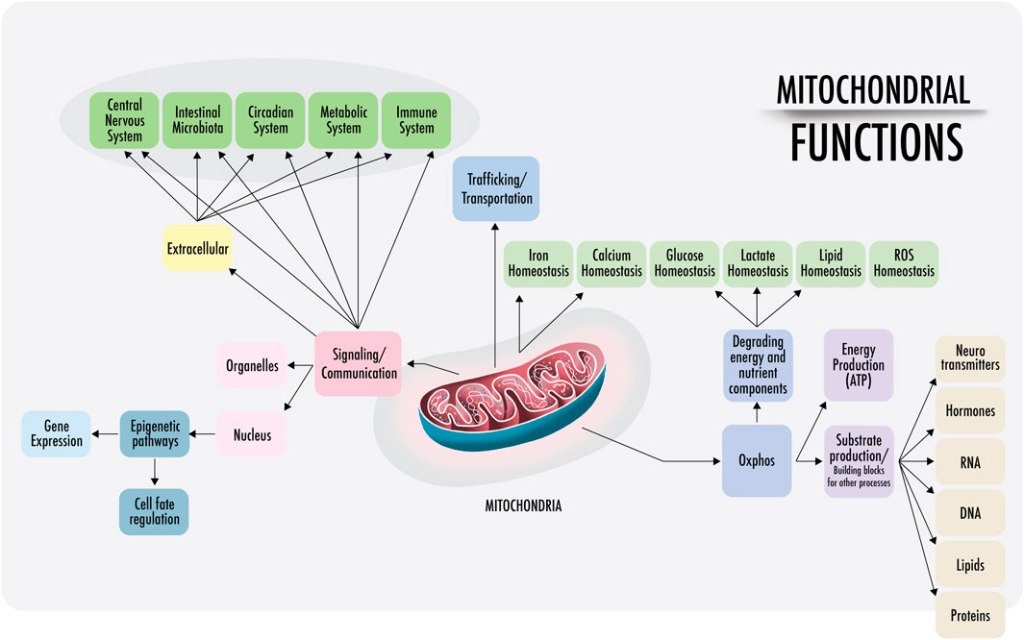

While we are concerned with the role mitochondria play within metabolism, it is worth noting that their function for human health and disease is manifold. The new view on mitochondria is that they have an integral role in human health, acting not just as autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine intermediaries, but rather as the alpha agent, in addition to their acclaimed act in ATP assembly.

Source: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/physiology/articles/10.3389/fphys.2023.1114231/full

Enter the Mitochondria: Oxygen for the Win

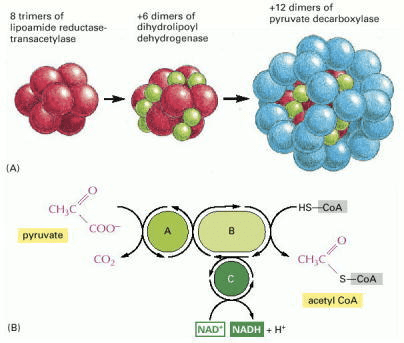

As we saw in stage two, the traditional view has been that pyruvate is the end-product of glycolysis. However, it is worth noting that the more recent viewpoint is that lactate is the true end-point of glycolysis. If O2 availability is adequate, pyruvate/lactate can then serve as a major substrate for oxidative metabolism. Pyruvate/lactate are shuttled across the mitochondrial membrane from the cytoplasm into the mitochondria via monocarboxylated transporters. Once inside the mitochondria, lactate is converted to pyruvate. Pyruvate is then rapidly decarboxylated by a giant, relatively speaking, complex of three enzymes, called the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. The products of pyruvate decarboxylation are a molecule of CO2 (often labelled a waste product, more on this below), a molecule of NADH, and acetyl-CoA. The acetyl-CoA molecule will be key to further energy metabolism, as we will see later.

Source: Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, et al. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4th edition. New York: Garland Science; 2002. How Cells Obtain Energy from Food. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK26882/

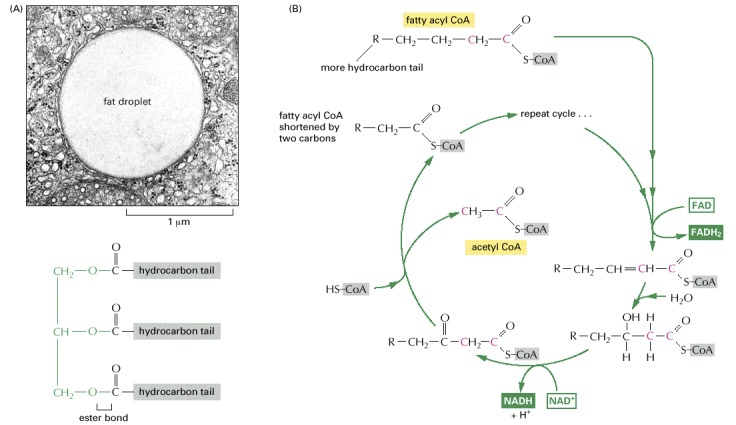

Fat Fashion FAD

Triacylglycerols (a.k.a. triglycerides) previously enzymatically degraded into a glycerol backbone and three free fatty acids enter the cytosol. The release of free fatty acids from triacylglycerols requires ester hydrolysis by an enzymatic process called lipolysis. Triacylglycerol molecules are unable to cross biological membranes, so their transport in and out of cells requires lipolysis and resynthesis. Once catabolized, the glycerol backbone can enter the pathway of glycolysis or gluconeogenesis (depending on the physiological conditions), but first, it must be converted into the intermediate glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate.

The fate of the free fatty acids from fat is catabolism to produce acetyl-CoA. Each molecule of fatty acid (as the activated molecule fatty acyl-CoA) is broken down by beta-oxidation. Beta-oxidation is a cycle of reactions that trims two carbons [this is where the “beta” term comes from as the second position structure of an organic molecule ultimately derived from the second letter of the Greek alphabet, beta (uppercase Β, lowercase β)] at a time from its carboxyl end, generating one molecule of acetyl-CoA for each turn of the cycle. Also produced in this process are a molecule of NADH and a molecule of the hydroquinone form of flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD in its fully reduced form FADH2).

Source: Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, et al. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4th edition. New York: Garland Science; 2002. How Cells Obtain Energy from Food. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK26882/

Bring Out the Big Guns: Acetyl-CoA and the TCA

Humans, like most non-photosynthetic organisms, access the majority of energy from sugars and fats. However, much of the useful energy that can be extracted from the oxidation of carbohydrates and fats remains stored in the acetyl-CoA molecules produced by the decarboxylation of pyruvate and beta-oxidation of fat from the reactions previously described. More energy is liberated from the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA cycle, a.k.a. citric acid cycle or Krebs cycle) of reactions, where the acetyl group in acetyl-CoA is oxidized to CO2 and H2O.

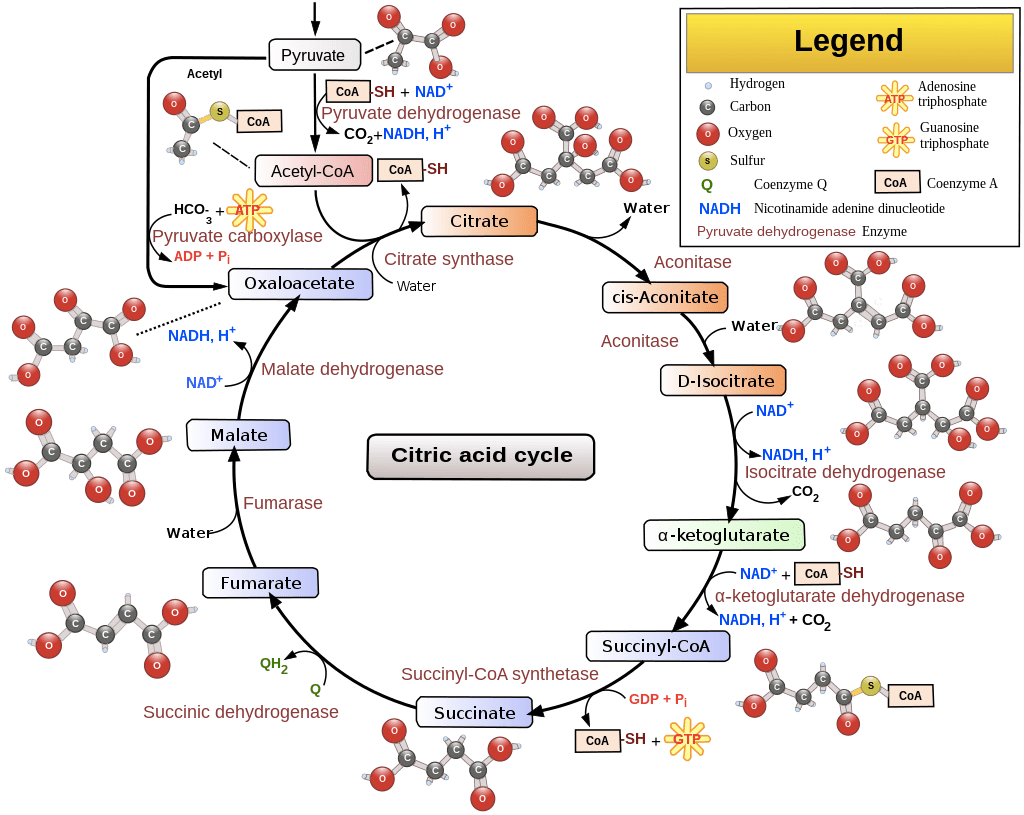

Oxidation Overdrive: The Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle

Enormous efforts took place in the 11930s HE to define the pathways of aerobic metabolism. After it was discovered that different metabolic endpoints occurred depending on the presence or absence of O2, attempts were made to understand why in the presence of O2 (i.e., aerobic conditions) certain organisms could consume O2 and produce CO2 and H2O. Eventually, in 11937 HE, the study of the oxidation of pyruvate led to the discovery of the tricarboxylic acid cycle. The tricarboxylic acid cycle is a series of reactions carried out by eight enzymes that completely oxidize acetate, a two-carbon molecule in the form of acetyl-CoA, into two molecules each of CO2 and H2O. The tricarboxylic acid cycle metabolic pathway connects carbohydrate, fat, and protein metabolism as the substrates can be interconverted via the cycle, with the exception that protein cannot be made anew (though there is ample evidence of protein recycling).

The tricarboxylic acid cycle takes place inside the mitochondria of eukaryotic cells. First, the acetyl group is transferred from acetyl-CoA to a larger, four-carbon molecule, oxaloacetate, to form the six-carbon tricarboxylic acid, citrate. This is where the alternate name, the citric acid cycle, comes from as citrate is the ionized form of citric acid predominant at biological pH levels. The citrate molecule is then gradually oxidized, allowing the energy of oxidation to be harnessed to produce energy-rich activated carrier molecules. Each turn of the cycle generates two molecules of CO2, three molecules of NADH, one molecule of guanosine triphosphate (GTP), and one molecule of FADH2 (though this can vary depending on the substrate/reactants). The chain of reactions is a cycle because at the end oxaloacetate is regenerated and enters a new turn of the cycle recombining with another molecule of acetyl-CoA to form citrate.

The sum of all reactions in the tricarboxylic acid cycle is:

Acetyl-CoA + 3 NAD+ + FAD + GDP + Pi + 2 H2O →

CoA-SH + 3 NADH + FADH2 + 3 H+ + GTP + 2 CO2

Where “CoA-SH” is Coenzyme A when it is not attached to an acyl group, “Pi” is inorganic phosphate, and “H+” is the hydronium ion. A schematic overview of the cycle is depicted below.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Citric_acid_cycle

The tricarboxylic acid cycle accounts for approximately two-thirds of the total oxidation of carbon compounds into CO2 in most cells. Carbon dioxide is often referred to as a waste product of the metabolism. However, labelling CO2 as a waste product does a disservice to the intricacies of physiology, negating the vital role that CO2 plays in the human body regulating blood pH, respiratory drive, and O2 affinity for hemoglobin. Post-production, CO2 is not immediately removed from the body. Rather it must first exit the cell and enter the bloodstream where it exerts its physiological influence before travelling to the lungs where excess CO2 is off-loaded to the environment to maintain homeostasis.

Though not directly involving O2, the tricarboxylic acid cycle is dependent on O2 to proceed in order to efficiently rid NADH of its electrons and regenerate the NAD+ to maintain the cycle. For a complete account of the cycle, clocking the count of carbon atoms, click here.

In addition to lactate/pyruvate and fatty acids, some amino acids can pass from the cytosol into the mitochondria, where they can also be converted to acetyl-CoA or one of the other intermediates of the tricarboxylic acid cycle. The tricarboxylic acid cycle also functions as a starting point for important biosynthetic reactions by producing vital carbon-containing intermediates. These substances can be transferred from the mitochondrion back to the cytosol, where they serve as substrates for anabolic reactions.

Regardless of the starting substrate, sugars, fats, or proteins, in the eukaryotic cell, the mitochondrion is the Rome toward which all energy-yielding roadways lead.

Each turn of the tricarboxylic acid cycle results in the formation of four molecules of the coenzyme electron carriers in their reduced form, three molecules of NADH and one of FADH2. These electron donors can shuttle high-energy electrons along with hydrogen to the membrane-bound electron transport chain, eventually combining with 02 to produce H2O.

All Aboard! Last Stop: The Electron Transport Chain

“Life is nothing but an electron looking for a place to rest.“

The last step in the chemical degradation of a foodstuff is the money shot. The majority of the chemical energy released occurs in the final process where the electron carriers NADH and FADH2 transfer the electrons obtained oxidizing other molecules to the electron transport chain. The electron transport chain consists of a series of four protein complexes that couple redox reactions, creating an electrochemical gradient that leads to the creation of ATP when coupled with chemiosmosis during oxidative phosphorylation. As electrons are passed along this specialized chain of electron acceptor and donor molecules, they fall to successively lower energy states. The energy released by the electrons is dissipated as heat and used to pump hydrogen ions (H+) from the mitochondrial matrix to the intermembrane space creating a proton gradient.

Source: Ahmad M, Wolberg A, Kahwaji CI. Biochemistry, Electron Transport Chain. [Updated 2022 Sep 5]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526105/

Dam, How Do Cells Breathe?

In the 11940s HE, the mechanism by which cells obtain energy from the breakdown of glucose in the absence of oxygen, i.e., glycolysis, was elucidated. During glycolysis, some cellular currency is invested, that is, the hydrolysis of ATP to liberate phosphate and eventually create more ATP later in the reaction chain. As the age-old adage suggests, “You have to spend money to make money,” and it seems biology had this rule figured out well before the Roman playwright Titus Maccius Plautus allegedly cited the phrase around 9800 HE. After an initial energy investment, phosphate groups are directly transferred from sugar molecules to ADP forming ATP. The pathway is pure chemistry, with one-to-one molecular ratios, therefore obeying the laws of stoichiometry. However, when scientists attempted to apply the same stoichiometric laws to aerobic respiration, they ran into the problem that the equations did not balance. The exact amount of ATP produced per oxygen molecule consumed varied, averaging out at around 2.5 ATP molecules (roughly 28–38 ATPs per glucose). The conclusion eventually was that aerobic respiration is not stoichiometric, it’s really not chemistry.

In due time Peter D. Mitchell proposed the proton motive force or chemiosmosis hypothesis (Mitchell 1961). In essence, chemiosmosis works much like a hydroelectric dam. The energy released by the oxidation of food is used to pump protons across a membrane (the dam) creating an effective proton reservoir on one side of the membrane. Protons then can flow back through the turbines, the amazing protein complex ATP synthase embedded in the membrane. In much the same way that the flow of water through mechanized turbines of a hydroelectric dam generates electricity, ATP synthase generates ATP by utilizing the proton motive force to phosphorylate ADP. The gradient nature of chemiosmosis explains why respiration is not stoichiometric but rather graduated.

Power of Protons

The proton gradient serves as a source of energy. Like a battery being tapped to drive a variety of energy-requiring reactions, the most prominent of which is the generation of ATP by the phosphorylation of ADP.

Oxygen: Our Ultimate Acceptor

At the end of the electron transport chain, the passengers need an exit strategy. The electrons are passed to molecules of oxygen gas (O2) that have diffused into the mitochondrion and simultaneously combine with protons (H+) from the surrounding solution to produce molecules of water (H2O). This metabolic H2O is accounted for in the image below as 10% of your daily water intake which is labelled as “Metabolism” on the left. The electrons are now at their lowest energy level, and the available energy has been extracted from the food molecule metabolism.

Source: https://socratic.org/questions/what-percentage-of-water-is-lost-through-the-respiratory-system

In total, the complete oxidation of a molecule of glucose to H2O and CO2 produces about 30 molecules of ATP. In contrast, only two molecules of ATP are produced per molecule of glucose by glycolysis alone. The availability of oxygen significantly increases the cell’s capacity to liberate energy!

Incredible Biological Efficiency

Amazingly, nearly half of the energy that could theoretically be derived from the oxidation of glucose or fatty acids to H2O and CO2 is captured and used to drive the energetically unfavourable reaction of ATP synthesis (Pi + ADP + energy → ATP + heat). By contrast, internal combustion engines have a maximum thermal efficiency greater than 50%, but most road-legal engines are only approximately 20% to 40% efficient when powering a car. For an electric vehicle, energy efficiency enlarges to an enormous estimate of 90%! In the human body, the inefficiency of energy metabolism is released by the cell as heat, making our bodies warm, which is not a bad loss of energy.

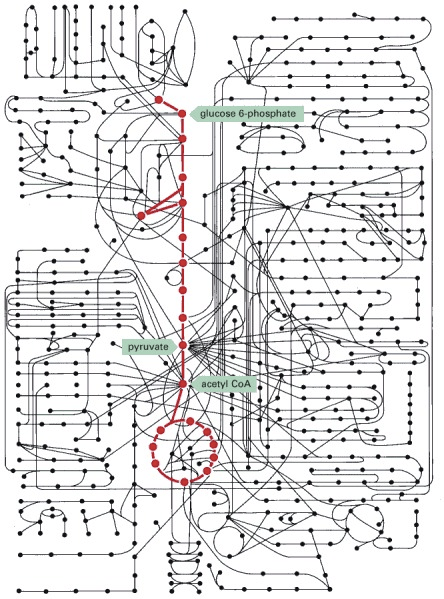

At the Centre of Metabolism: A Conclusion of Sorts

This was an incredible oversimplification of the immense intricacy of the chemical machinery of a cell. To give a sense of the complexity, check out the chart below, where the central pathway of glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle are shown in red in relation to the other metabolic pathways. Even this type of chart represents only some of the enzymatic pathways in a cell. Only a tiny fraction of cellular chemistry was touched upon above, but hopefully, it was enough theory for a better understanding of practical application.

Source: Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, et al. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4th edition. New York: Garland Science; 2002. How Cells Obtain Energy from Food. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK26882/

How To Train

Now that we’ve covered the theory, how can we put that into practice to optimize training? This will be the subject of future posts…

6 thoughts on “Energy’S UP: Instalment Five. Methods of Metabolism”