Saturday, September 16, 12023 Human Era (HE)

This is a continuation of previous posts. For parts one and two of the post, click here (1.0) and here (2.0), respectively.

Let the Race Begin

As the sit-down paddlers set out, I lined up at the start line with the other distance SUPers. The starting sound sounded, and we were off. Initially, it was at a slightly quicker pace but then quickly settled into a comfortable pace. We were in it for the long haul.

Quite quickly, the group started to separate. There were the fastest paddlers pulling ahead to my far left, taking an inside line. Closer, but still ahead and to the left, was a second group of paddlers. Myself, and a few others, formed a third cohort. I was happy to be near to another Wavechaser to have a general gauge of pace. Otherwise, I was mainly blind to how fast to paddle in comparison to the other racers and, more specifically, over such a distance.

Deftly Drafting

I took advantage of the company and pulled into the slipstream of my fellow competitor. It is estimated that you can save up to 30% of your energy by drafting. Another cool aspect of drafting, at least in theory, is that if the draft train is stable, it may be that all the SUPers involved benefit from the effectively longer water line of the draft train. The theory is that the series of SUPs simulates one long board rather than a series of single separate SUPs. I am slightly skeptical since the water sections between SUPs would serve as a soft spot in an otherwise sturdy hull. Nonetheless, if the theory is true, then the effective hull length would be longer, allowing for a faster top speed (since a longer board can go faster).

SUP Sipping Schedule Segue

My GPS watch vibrated, signalling the completion of the first kilometre. I took a sip of my super solution. My plan was to time my drinking intervals to each kilometre. The reported maximal fluid absorption rate of the stomach is approximately one-litre per hour. However, it is worth noting that gastric emptying depends on factors like volume, energy density, osmolarity, pH, exercise intensity, and stress. Commonly referenced exercise hydration guidelines suggest consuming approximately 250 millilitres (7-10 ounces) of fluid every 15 minutes. According to my mental mathematics, I would need to consume around 125 millilitres of fluid each time my watch buzzed me for a completed kilometre assuming my anticipated pace of seven to eight minutes per kilometre was acutely accurate.

The Galpin Equation

Conversely, an alternative informed estimation would be to use the “Galpin Equation.” The equation is to use your bodyweight, in pounds, divided by 30 to determine the amount of fluid, in ounces, that you should consume during intense exercise every 15 minutes. For example, a 180-pound athlete vigorously exercising should consume 6 ounces of fluid every 15 minutes. For the non-imperialist, an easy conversion for the metric system would be to multiply your bodyweight in kilograms by two. For example, the 180-pound athlete would be 81.8 kilograms (the conversion factor is 2.2 pounds per kilogram), so they should consume approximately 160 millilitres of fluid every 15 minutes. Six fluid ounces are around 177 millilitres. The conversion factor for ounces to millilitres is approximately 29.6, which is how the math works out.

Drawn-out Drafting Details

Perhaps it was placebo, but I felt I was feeling the benefits of drafting, despite being barely past the first kilometre of the race. Feeling fresh from the fuller-than-faint force reduction and knowing the theoretical benefits of being in a draft train, I wondered if we could catch the next group of SUPers up ahead. With a bit of a push (and more than a hint of hubris), perhaps we could tag onto their train. I pulled out of the slipstream in an attempt to take the lead of my self-appointed paddle partner and proposed my plan while poised in parallel pursuit. I immediately realized how much more energy was required to keep the pace. Thankfully, he had much more insight and assured me we were in a good position, given the racers who were ahead and the pace that they were setting. Heeding his wisdom and experience, I realized it would be best to conserve my energy. I ebbed my enthusiasm and etched my edges back to the end of his board and entered an exercise of entrainment.

As we approached the first turn, we were scattered amongst a few qajaqers. Despite the contestant congestion, there was enough spacing for an easy turn. I must have let up on my pace leading into the turn, or my racemate had sped up, since after the corner I was no longer in his slipstream and would not enter it again. I put in a minor attempt to catch up but I was fearful that the increased effort would come back to haunt me later. So I relented, resigned to remain in the rear. In hindsight, perhaps if I had pushed a bit harder to regain the draft, it would have benefited me in the long run. But in the moment, it felt like too costly of a compromise. I was attempting to regulate my metabolic effort levels via nasal breathing to ensure I was mainly in an aerobic oxidative phosphorylation state with minimal by-product formation in order to ensure a prolonged exercise effort.

Solo SUP Section

The next target was the gap between Boulder Island and Hamber Island. After clinging to the coast between Maple Beach and Cod Rock the procession of paddlers peeled away from the shoreline. At this point, I was paddling on my own and began to prepare my psychology for the prolonged push.

I passed a group of recreational qajaqers who tried to cross the gap between myself and the paddlers I was pursuing. They cut it pretty close, and I was slightly annoyed that they had not been more patient to let me pass. Though in hindsight, I suppose the gap between myself and the paddlers in my pursuit was possibly plus petite.

As I approached Hamber Island Lighthouse, a qajaqer on my left was negotiating the corner. The short course was a left turn around the lighthouse before heading to Grey Rocks Island for another left leading back to Whey-ah-wichen.

I continued on keeping the lighthouse to my left, and now aiming toward Hamber Island. Another group of recreational qajaqers were scattered around the south end of Hamber Island but thankfully were not in the way.

On the north end of the island, it felt like there were a few small bumps coming from behind coaxing me on. I had a few flashbacks to past paddles through this section of water as my mind wandered in the monotony of paddle strokes. I was approaching Bikini Island and I thought back to vTNR#1 and vTNR#7.

I snapped back into reality with the realization that I could hear paddle strokes behind me. At least I thought I could. In my mind’s eye, I thought the turning point for the medium-length course was Bikini Island. I set my sights on getting there without getting lapped by the shorter-distance cohort. The ego is an interesting thing, but I knew that getting lapped by the group that set out a short time after me would be demoralizing. So I was determined to (try) not let it happen. In hindsight, I realized that the medium-course turning point was Jug Island, so there was still ample room for me to be passed and have my ego crushed.

Jug Island: Losing Track

Fortunately, I was able to make it to Jug Island before being lapped. However, I was informed by a medium course participant that they were close behind me with the goal of gobbling me up (my cousin in Belgium used to say that when you passed someone in a car you ‘gobbled them up’ and the saying has stuck ever since).

It was somewhere after Jug Island, en route to Racoon Island, that I lost track of distance. When my watch buzzed mid-way between the islands, I realized I had forgotten which kilometre I was on. I knew it was around seven kilometres, plus or minus one. But, was it six, seven, or eight? For sure, I could have looked at my watch, but there was a part of me that did not want to know. I would be elated if I was already at the 8-kilometre mark but dejected if I was only at the 6-kilometre mark. Plus, I worried that once I looked at my watch, I would be open to obsessively checking it for the rest of the race. The seal would be broken.

Then it dawned on me. If I just waited until after rounding Twin Island, the next kilometre ping would be the midway mark. I forgot about forgetting my account and focused on getting past Racoon Island.

Getting Caught

It was on the north side of Racoon Island that I realized that I had a paddler in close pursuit. I had suspected their presence earlier, but now I was certain, as I could see them in my right periphery. My male chauvinism came to the surface when I realized that it was a woman, and I found myself fabricating figments about whether she was in the race or just out for a leisurely paddle. It would have to have been a very non-leisurely paced leisurely paddle for my imagined scenario to ring true.

Snapping back to reality, I put up a bit of a fight, picking up my pace before coming to the conclusion that my quickened cadence was unendurable. As we neared the southern tip of the southmost Twin Island, it seemed the sea gods sensed my ego beginning to bruise and bolstered my battle with some baby bumps from behind. We were neck and neck for a few moments before she pulled away as we went into the turn at the island. I put my prejudice aside and mentally nursed my bruised ego as she gobbled me up.

Sex and Sport

Here is where I wish I had paid more attention to the pre-race debriefing. As mentioned, my recollection was that participants could draft anyone in the same race event as them. There did not seem to be a sex distinction. So, in the heat of the race, a confluence of mental heuristics took hold.

Outside of the race setting, my gut instinct is that there should be a separation between male and female sports competitions since there are biological differences that result in different physiological outcomes. In fact, the most established determinant of difference between male and female athletes is the proportion of lean body mass. Interestingly, the level of lean body mass between the sexes is most determined by your hormone levels during adolescence, which to me should therefore serve as the determinant for future participation of females transitioning to males in sports competition. That is, if you experienced the sports performance benefits of a more masculine hormone profile during adolescence, then you should compete as a male later in life due to your larger lean body mass. For a great podcast that covers some of these concerns, check out this episode of the BBC‘s The Inquiry, “Is Women’s Sport In Trouble?“

However, in the heat of the race my gut instinct seemed to go against my not-in-the-moment, non-fatigued, and not believing there was a rule regarding intersex drafting self. My fatigued body and brain either truly believed intersexed drafting was legal or convinced me of such. Either way, the outcome was that after a bit of paddling close behind this other paddler, I decided to slide into their (to be clear, I completely believe them to be a her here, but used the gender-neutral term for emphasis) slipstream along the backside of the Twin Islands. I was gassed at the time, and in hindsight, I can see the argument going either way as to the ethics of intersex/gender sports participation. At the end of the day, it comes down to the rules, which I believed to be pro-intersexed drafting at the time.

Revisiting Rules

However, in the process of writing this blog post, I revisited SUPBoarder.com’s post on drafting and noticed that the SUPAA rules listed explicitly state that drafting is, “Not allowed out of board class or gender.” In hindsight, this statement left me questioning my assumption that intersex drafting was legal in this event. Assuming it was allowed, as per my recollection of the debriefing, then there is no issue. However, if it was, in fact, a rule for this race, then technically, I cheated.

A Post-Mortem Addendum

Much later I did come across evidence to suggest that my belief that intersex drafting was legal for this race. For the Board the Fjord race, which is organized by the same sporting body as the Whey-ah-wichen Whipper, the rules do state that men and women can draft each other provided that they are in the same craft category. I must have read this in the Whipper registration or heard it in the race briefing. In any case, it feels good to be vindicated as not being a cheater. But I will leave in my musing on cheating that was composed when I was uncertain to my cheating status nonetheless.

Hypothetical Arguments In Case I Inadvertenly Cheated

A few weak defences come to mind in case I did cheat, and I will explore them here mainly as a cognitive curiosity, as I don’t think I actually did cheat. The first (very weak argument) is that the rules were from 12015 HE and may have changed since then. Though, a quick internet search seemed to suggest that the ISA rules were still the same. The second is the ‘no harm, no foul‘ clause. Did I mention these are weak arguments. From the perspective of this argument, my drafting had little to no effect on the outcome of the race, so who cares. The third, which is much more loose, would be the use of the term, “gender,” in the rules is misleading. I side with the view that gender more accurately describes “the behavioural, cultural, or psychological traits typically associated with one sex.” Gender in this view is more of the social/cultural role one plays or is seen to play, rather than the biological difference between male/female sex (which to be clear is much less black and white than most of us realize). Although I am aware that the definition is not universal, has changed significantly over the last 500 years of usage, and in colloquial language, the two terms are used interchangeably. All the more reason that a rule book should be more precise with its language, rather than rely on ‘gender’ as a stand-alone term.

Thus my tongue-in-cheek rebuttal to the possible rule infraction would be that there was no way for me to determine the social role that this SUPer identified with within our current 121st century (HE) gender-identified new world order. Therefore, there was no way to tell if I was drafting a man or a woman. And, as the following will discuss, technically, the male/female distinctions in sports rest arguably arbitrarily on a set of standards for within-sex sports competition based on the belief that levels of naturally occurring performance-enhancing biomolecules (e.g., testosterone) dictate fairness of competition.

Exogenous Versus Endogenous

Variety is the spice of life. There are natural variations in the production of the bodily biomolecules. The levels of which are subject to the influences of nature and nurture. Athleticism also arises as a result of interactions between nature and nurture. For example, success in a sport like basketball is highly influenced by height which results from a complex interaction of genetic, biological, and environmental factors. An individual’s level of testosterone during adolescence affects the release of growth hormone and thus can affect their height, though the results are far from a deterministic outcome.

Mr. T. The Other Mister Tough.

Testosterone is envisioned as the major contributing biological factor to sex differences in athletic performance. This is most likely the result of testosterone’s effect on lean body mass development during growth and maturation. This fact is central to the main argument to have sex classifications in athletic competitions, as an attempt to level the playing field and ensure fairness. This is also one reason that testosterone is banned as a performance-enhancing substance, along with the fact that excess exogenous testosterone can result in short-term and long-term negative health consequences. In addition, as an anabolic steroid, most people are familiar with testosterone use in bodybuilding to increase muscle mass. But what is often overlooked is the role of anabolic steroids in speeding up recovery. For an excellent, albeit older account of how steroids were used to boost performance in track and field sprinting, check out Charlie Francis and Jeff Coplon‘s “Speed Trap: Inside the Biggest Scandal in Olympic History.” The book is a direct exposé of Canadian sprinter Ben Johnson‘s infamous 100-meter run at the 1988 Olympics, revealed by his coach, Charlie Francis, and presents his account of the events and how steroids allowed Johnson to train at peak levels (along with essentially all the other athletes in that race). Anabolic steroids improve performance by allowing athletes to train harder with higher volume and intensity, thereby increasing their training stimulus.

Back on the endogenous front, things get thornier when you consider that there are differences in the naturally occurring levels of testosterone both between and within the sexes. Hardly anyone argues for a limitation in who can participate in basketball due to their natural endogenous hormone levels. Yet it is most certain that many of the athletes who make it to the highest ranks of basketball benefit in some way from being on the higher side of the endogenous hormone spectrum. In fact, there are a host of sports in which biological variations bordering on biological conditions are known to provide performance perks. Arguably, for many elite athletes, what makes them exceptional in their sporting endeavours is that they are outliers on human physiological variables.

Yet, as Mayaan Sudai points out in a 12017 HE paper, “The testosterone rule—constructing fairness in professional sport,” the two large-scale studies aimed at assessing hormone profiles in elite athletes revealed conflicting results. The first investigation dubbed the GH-2000 study, concluded that elite athlete’s hormone profiles differed from the typical reference range and that the International Olympic Committee’s definition of a woman as someone who has a normal testosterone level is untenable. The second study deemed the Daegu Study, was aimed at better defining the Athlete Biological Passport of a woman by measuring the serum androgen levels among a large population of high-level female athletes. The results revealed that despite the speculation that elite sportswomen would demonstrate higher testosterone levels than their non-athlete counterparts, the median testosterone levels among elite female athletes were similar to those of non-athlete healthy young females.

Sudai highlights how two camps have formed based off of the findings from these investigations. On one side, “Natural testosterone levels do not provide a competitive edge, and therefore hyperandrogenic female athletes should compete as women.” On the other side of the argument, “Testosterone levels do provide a competitive edge, and therefore hyperandrogenic athletes should not be allowed to compete as women.” Sudai goes on to outline three distinct courses of action. One option is to “Keep male–female categories, but follow gender identity.” Another option is to “Neglect male–female categories for a better biological indicator.” The third option is to “Start over,” and follow something akin to the International Paralympic Committee with a multi-tier classification system applied to a battery of physiological variables identified as key performance metrics. I will leave you to read through Sudai’s arguments to come up with your own conclusion.

Seemingly Simple to Completely Complex

Bringing it back to basketball, indeed, evidence from an investigation aimed at assessing the endocrine profiles of elite athletes demonstrated that basketball players were among the athletes with elevated testosterone levels. Although, it is worth noting that the measurements from the study were one-time values taken after a competition, and thus, not necessarily reflective of the levels throughout growth and development, as per my contention above, for the benefit of increased lean body mass. Contrast this with track and field, where there are recent cases of female athletes being banned from participation because of elevated endogenous hormone levels and a conundrum crops up. Not to mention the controversy of gender fluidity involved in collegiate swimming.

I did a segue section on sex in a post that went into the weeds on what is a woman after a few conversations with friends on the topic and a YouTube prompt to watch Matt Walsh‘s film by that very title, “What is a Woman?” A simple summary of the segue is that it is not as simple as we believe, particularly when you consider the full spectrum of natural biology and our social and cultural practices.

Dope Man, Dope Man

With respect to sport, I think it is easy for us to make a clear distinction between endogenous and exogenous hormone levels. At least in theory. In practice, it may be more difficult to truly assess the difference, with techniques like micro-dosing to beat the biological passport or the possibility of gene doping (which in my opinion is likely already in practice, though no cases have yet been reported). It would be easy enough to have distinct competition categories for athletes to select and participate based on their own ethics/values and health risk tolerances to the use of performance-enhancing substances (a fourth additional option to Sudai’s suggestions above). The overarching question of society’s ethics and health risk tolerance looms in the background.

Bigger, Stronger, Faster Fears

My personal belief is that the health risks of performance-enhancing substances are often overblown in the media. While I would not argue that they carry zero risk, many of these substances are used medically (e.g., anabolic steroids) or daily (e.g., caffeine, the most commonly consumed psychoactive drug in the world, and thus arguably the most commonly consumed PES) with minimal adverse health effects. The 12008 HE documentary Bigger, Stronger, Faster*, critiques our cultural inconsistencies around drugs, cheating, and success, and highlights the fact that steroids are less risky than commonly portrayed. Though, it is worth noting that one of the brothers featured in the film, Mike Bell, died shortly after the film was released at the age of 37. Most likely, this was due to substance use issues around painkillers, rather than a direct result of steroid use.

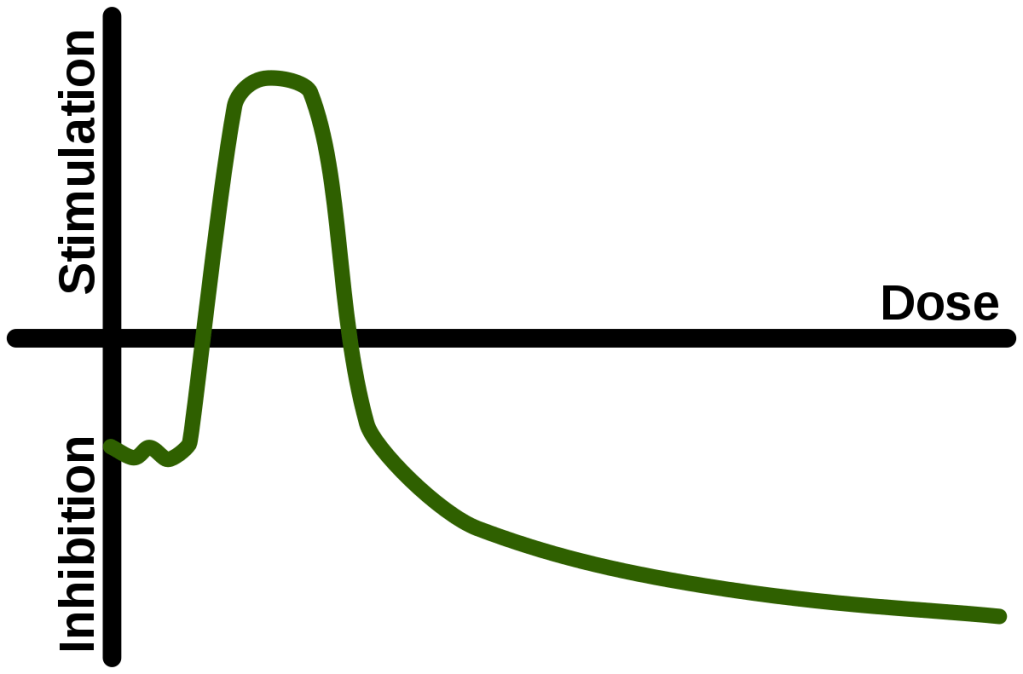

From Hormones to Hormesis

Like many processes within biology, there is a dose-dependent response, commonly referred to as hormesis in toxicology, biology, and medical jargon. I have always been a fan of the adage, “Too much of anything can kill you.” But perhaps the saying should be caveated with, “So too, will not enough of something.” According to the principles of hormesis, too little, and you will not gain an effect. Too much, and it will cause harm. You need to be Baby Bear, just right, to reap the rewards. I love the concept of hormesis, that small stresses at the right time can make us stronger. I bring it up ad nauseam with clients in the clinic in order to educate them about the stress-adaptation response to exercise, specifically, and of organisms, generally. From hydration and medication to ionization radiation and physical education, hormesis paves the way to organism modification augmentation.

Last Little Lines

I have focused on testosterone as the hormone du jour. But I would be remiss if I did not make mention of human growth hormone or hGH. At the risk of angering soccer (cough, football) fans, it is my opinion that Lionel Messi does not become the legend and arguably the greatest soccer player, some would even say athlete, of our time and history, without growth hormone. While I will acknowledge he is a phenomenal athlete, I am more partial to the more traditional lists of greatest athletes culminating in Michael Jordan (at least from the modern sporting era – who knows how the ancients would fare). Although some of the arguments put forward in the article above are convincing, mainly the universality of football (cough, soccer), meaning that he competed against a larger athlete pool. Todd Hargrove makes a compelling case for why a football athlete, generally, and Messi, specifically, is the world’s best athlete. One point is that football requires more coordination (i.e., greater athleticism) than other multidirectional sports since players must coordinate moving the sports ball while locomoting with the same set of limbs.

Regardless of the status of greatness achieved, my point is that Messi does not make it to the level of eliteness he accomplished without the help of modern medicine. Messi was diagnosed with growth hormone deficiency at the age of 10 and was treated with exogenous growth hormone in order to reach normal levels and progress through normal growth and development. As per our biological variability chat above, Messi got the short end of the stick (pun intended) on the natural physiological variability spectrum (granted he was at the extreme end of natural in the realm of pathological). While it may be that without supplementation, he would have still achieved the same greatness, I am doubtful a mini-Messi would succeed at such a miracle. He was obviously good enough as an athlete for FC Barcelona to fund his treatments. Messi had a level of innate ability that was noticed before he began treatments. Despite this, I doubt a diminutive duplicate delivers ditto deeds of disport. Arguably, the interaction between nature and medical nurture may have worked in his favour. It could be that his low centre of mass is a byproduct of his early lack of growth hormone and conferred an advantage for balance, strength, and agility. Or even forced a higher level of skill development at an early age, which, when augmented with adequate hormones, heightened his potential (sorry, could not resist… call the pun police). There are many speculations to be made.

Notwithstanding growth hormone supplementation, I am skeptical that Messi would have been able to grow, develop, and train at the levels that would have allowed him to achieve his current greatness. Messi is a marvel of modern medicine.

Segue Summary

All this is to say that I drafted a woman in the Whey-ah-wichen Whipper. It may have been cheating. Maybe it wasn’t. Equal rights. Gender equality. Acute fatigue compromises to my cognition. Sports start over based on physiological variables. She obviously had a higher aerobic capacity than me. Pick your justification… now where were we in the race.

Audio Addendums

Recently, I have come across two podcasts that reminded me of writing this post. One was an episode from Andy Galpin‘s podcast, Perform, titled, “Genetic Testing for Sports Performance,” that gives a good overview of genetics, their implication regarding sport performance, as well as gene testing and doping. The other was a series called Tested, prodcuced in collaboration by the CBC and NPR, which explores the convoluted history of women’s participation in sport with a focus on the Olympics. Both the episode and series are well worth a listen for the curious mind. The commonality is a thread that demonstrates how convoluted genetics are and that biology is not binary.

6 thoughts on “Words on the Whey-ah-wichen Whipper (3.0)”