Sunday, March 16, 12025 Human Era (HE)

Preamble Ramble

This post is a continuation on energy metabolism and its relationship to stand up paddleboarding (SUP) that covers the philosophy and physiology of energy systems training. To go back to the start, click here for the first instalment. Or pick your way through the chronicle that was.

Physiological Performance Parameters

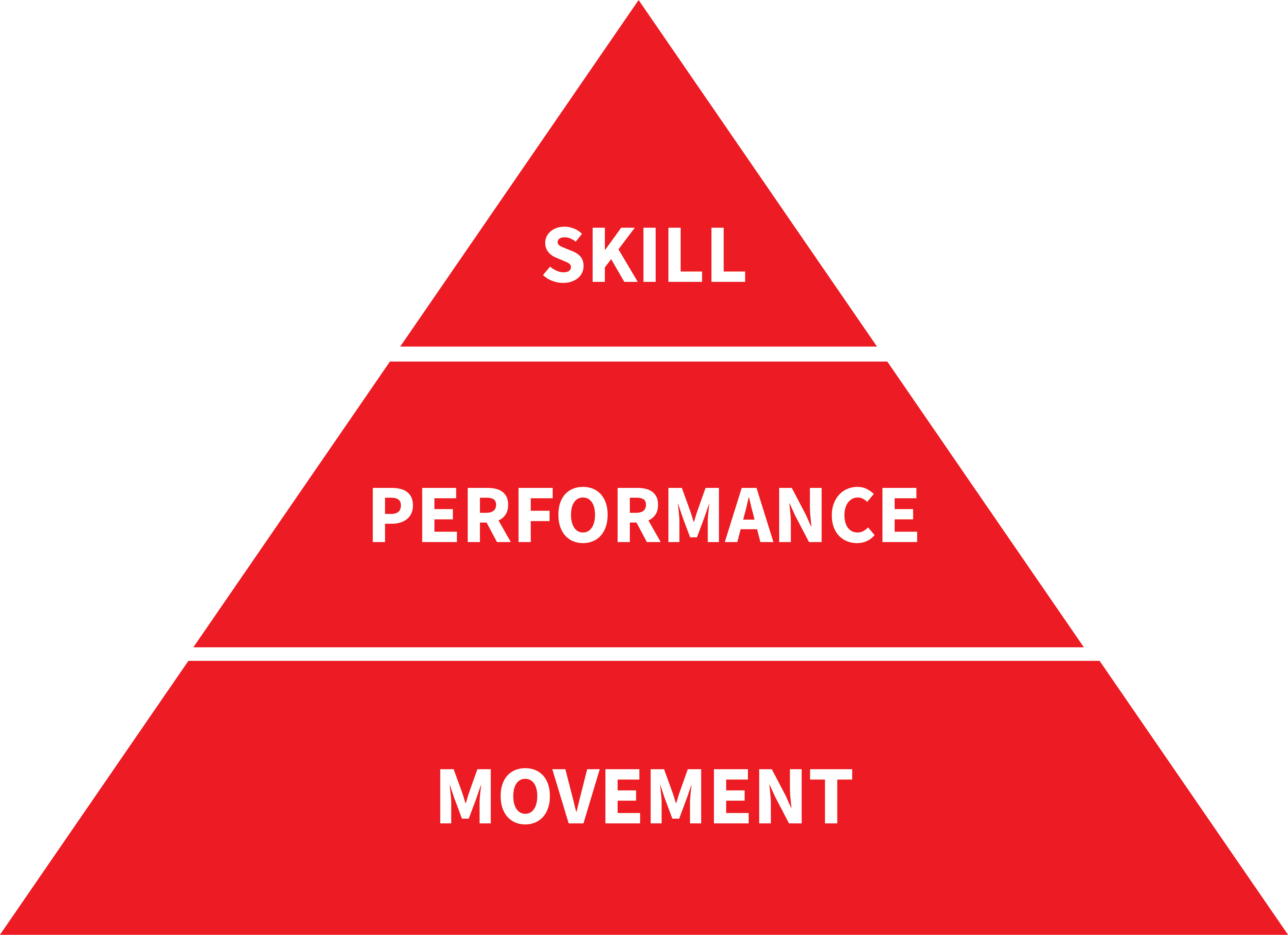

Larry Cain’s blog has an excellent summary of what fitness elements are essential for SUP success. Cain highlights the meta-categories of strength, power, energy systems, flexibility, and board skills. Looking at his table reminds me of Gray Cook‘s 12003 HE book “Athletic Body in Balance” where he introduces the optimal performance pyramid, which is an idealised progression of human movement culminating in specific sports skills (see image below). Essentially, the foundation on the pyramid is basic movement, which is comprised of things like flexibility, range of motion, mobility, stability, and proprioception. The performance platform refers to parameters such as endurance, speed, strength, power, and agility. Whereas skills in this context are the sport specific skills (i.e., the board skills Cain refers to such as paddle technique, foot work, steering, pivot turns, etc.). While all of these parameters are important for performance in general and SUP specifically, for these posts, I am only concerned with the energy systems highlighted (i.e., phosphagen, glycolytic, and oxidative). In relation to the pyramid, the energy systems mostly come into play at the performance level, as they are the inputs to endurance, speed, strength, and power, which expressed in coordinated fashion is agility. Of course, movement requires energy, too, but for the purpose of this discussion, we’re focusing on higher levels of metabolism.

By considering training goals, proper focus to the appropriate energy system can be made. If your goal is to improve sprint speed/power, it makes little sense to train with parameters focused on oxidative adaptations. Specificity matters and a best practice approach would include preliminary assessments and tests to determine strengths and weaknesses for improved training focus and efficiency.

However, assuming a general improvement in capacity for longer distance endurance-type events, significant focus will include the oxidative system. Though, a well-rounded training regime must also incorporate efforts targeting the phosphagen and glycolytic systems, as in competition, they are needed for speed and power burst. At the same time, it is impossible to train the systems independently. They are all active, always, just to varying degrees. Omitting higher-intensity training efforts will limit the stress and adaptation of the phosphagen and glycolytic systems.

Viewed from another lens, look at the systems through the adaptation you are trying to drive. Whether that be improving fuel availability or clearing/recycling metabolites. For the former, the focus is more on oxidative metabolism, and for the latter, the focus should be on glycolytic metabolism.

Let’s delve back into the systems to find out why…

Levels, Zones, Domains, and Systems

For millennia humans have been exercising and training. Naturally, attempts to determine the best ways to drive physiological adaptation took hold. As is the case for many of the cycles of history, training tends to follow a revolution/counter-revolution pattern. Like the cycles of the seasons, things repeat but are never the same from one year to the next. Human training seems to follow this trend with similarities between training waves but differences from one iteration to the next.

Presently, a common training framework is centred around the FITT principle. Frequency, Intensity, Time (duration), and Type. Those variables are relatively self-explanatory and easy to quantify or categorise, with the exception of perhaps “intensity.” Intensity is a parameter that we all intuitively understand, but it is a bit harder to pin down with a precise definition. Essentially, intensity translates to effort, or more specifically, the quantification of energy expenditure. Traditionally, intensity was determined by speed measures for activities like walking or running. The faster the more intense. However, once outside the natural forms of human locomotion, e.g., using bicycles and watercraft, the relationship between speed and intensity is no longer as linear or reliable. With bicycles and watercraft, technological and environmental factors affect speed independent of intensity (e.g., gearing, vessel shape, wind, current, etc.) to a much greater extent. Another metric aside from speed is needed.

Enter Heart Rate Training

For thousands of years, humans have measured heart rate via pulses, noting its increase with activity. Without a doubt, prehistoric humans would have been aware of heart sounds, whether that be by hearing or feeling their own pulse or putting an ear to the chest of their peers. Technology to assess heart rate has a long history too. Over 200 years ago, the stethoscope was invented. Later, at the end of the 119th century HE, the first electrocardiogram (ECG) was invented, allowing for more efficient real-time heart rate monitoring. This invention was followed by a portable model, the Holter monitor. Then, in the late 11970s HE, Polar Electro came out with the first wireless ECG. There was now an accurate, efficient, objective, and practical way to measure exertion in real time. At this point, there was an increase in the use of heart rate as a measure to quantify exertion after a confluence of influences such as Per-Olof Åstrand (for research relating the volume of oxygen uptake to heart rate), William Haskell and Samuel Fox (for the famous “Fox formula” or 220-age to determine maximum heart rate), Martti Karvonen (for the heart rate reserve formula to determine training heart rate based off of your usable beats), and running researchers and coaches like Jack Daniels and Sally Edwards who popularized heart rate based training approaches.

For an excellent account and short story of the sports watch, check out the video below from the Global Triathlon Network.

But Wait… What Are We Trying to Measure?

When training, the stimulus applied is often conceptualized as training load. Because athletes are often pushing themselves to the limits of their capacities, the risk of overreaching and overtraining is present and significant. Monitoring training load is an attempt to minimize that risk as well as track what works (and does not) for the athlete.

Training load is an interaction between intensity and volume (or duration). Frequency also plays into the equation since it impacts the window of recovery in the stress/recovery adaptation cycle. Note that many of the benefits of training happen in the recovery window, not while training. However, the interaction between these variables is harder to quantify as individuality modulates the relationships. Attempts to quantify training load are determined by examining either external or internal factors or some combination thereof.

External Load

External load “is defined as the work completed by the athlete, measured independently of his or her internal characteristics.” I did a whole post on “work,” titled, “Energy’S UP: Instalment Two. Let’s Get to Work,” if you are exertion eccentric, then engage and explore. It is worth highlighting again the apparent difference between colloquial and technical differences in the definition of work.

Weird Words on Work

Work requires displacement (or movement), as it is the product of force applied over a distance. If an object is not displaced, then by definition, no work has been performed. The pseudo-paradox is that if you ask someone to hold an air squat and then inquire if they “working,” they most certainly answer yes. And, in fact, they are working, despite apparently not displacing their body in spite of applying force to their bones via muscular contractions by way of tendons.

Visualizing the work being done is a matter of scale and perspective. Macroscopically, the air squat appears to be stationary, and thus, it appears that no work is being done despite energy expenditure. But microscopically, nerves are firing and myocellular cross-bridges are cycling, meaning molecules are moving to keep the air squat static in space.

So, for work to occur, movement has to happen. It just might be that that movement is harder to perceive.

Back to Loading

A common example of external load is power output, which is commonly measured in cycling. In running, speed tends to be the external load measurement of choice [though power meters are available (well, sort of) for running and have improved over time]. In SUP, measures of power are also available but not presently in widespread use. Speed can easily be measured with GPS. However, the relationship between speed and internal measures of physiology on the water is less linear. External conditions like wind, waves, and current exert a far greater effect on SUP compared to other modes of exercise, creating a mismatch between external and internal load. Thus, a pertinent point pertaining to the probing of power proportions in paddlesport is precision.

Internal Load

Internal load is the “relative physiological and psychological stress imposed.” Thus, internal load is just as critical, if not more, in “determining the training load and subsequent adaptation.” From a purely metabolic perspective, internal load may be more reflective of the mortal matter milieu by making more materialistic measurements of metabolism.

Training Load

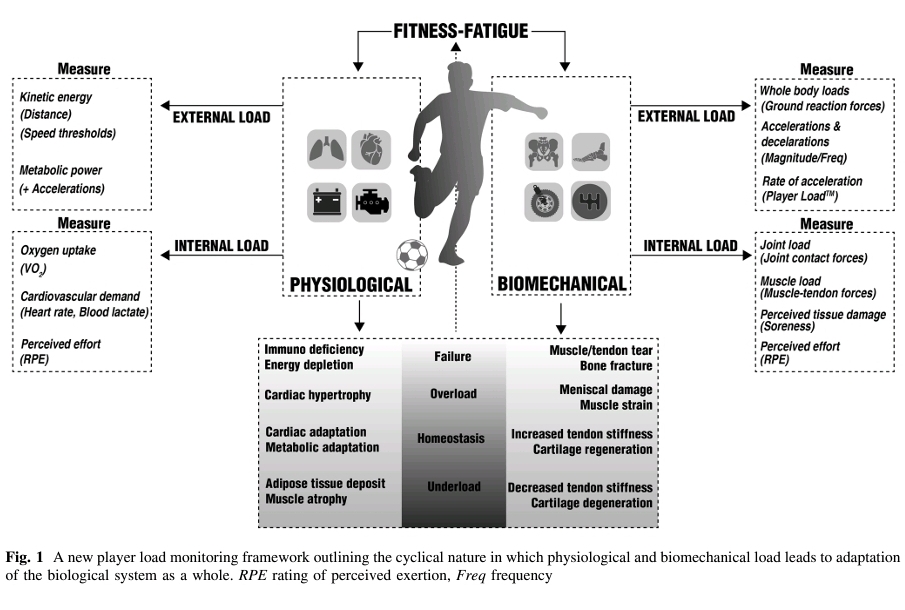

What we are ultimately interested in is overall load/stress on the body. Ideally, this needs to account for bioenergetics and biomechanics. While internal load is defined as the physiological load on the body, in my opinion, the construct and its assessment fail to highlight the mechanical strain on the tissue systems, that is, the biomechanical part of the equation. The physiological focus seems to overlook biomechanical stresses. Similarly, despite external load being a physical measure of work, it feels like most modern models miss measuring the biomechanical tissue strain, as they fail to account for factors like rate of force development directly and more regionally specific outcomes (e.g., joint stress). To be certain, external load as a surrogate measurement of work completed signals this physical/mechanical load/stress more explicitly than internal load. However, the data points collected are more global for whole body movement (e.g., GPS) versus being regional (e.g., lower extremities) or specific (e.g., left ankle joint).

Accelerometers and GPS data from fitness tracking devices are starting to do a better job of quantifying these loads, but presently, they remain systemic variables. Perhaps it is too tall an order to ask for regional or specific biomechanical load measurements. The hope/promise is that better algorithms may eventually reflect the biomechanical strain from existing technologies or a more dystopian future perhaps has us all equipped with implantable devices (the irony of course is that we are alreay equipped with biological mechanosensors). Conversely, perhaps in time, overall internal and external physiological and biomechanical measurements like resting heart and GPS/accelerometry will better predict localized joint stress.

Composite Measures

Already, several different proprietary-type models of training load exist from various companies that collate data from multiple inputs in an attempt to quantify training (e.g., heart rate, power, duration, speed). Ultimately, they come up short as a carbon copy of the true inner workings of the body, but they can serve as useful tools in the process to quantify the presently unqualifiable.

Whatever the future holds, I am not the only one presently pondering the biomechanical side of the story as is evident from the image below. The schematic is the best representation that I have come across that theoretically accounts for the internal and external loads at both the physiological (or metabolic) and biomechanical levels.

Interestingly, many coaches and some research suggests that the simple metric of rating of perceived exertion (RPE) for a session can be a useful (and arguably the best) internal metric of training load. Regardless of the veracity of this claim, a general consensus it is important to monitor both internal and external load parameters, as arguably, each measure is slightly biased.

Present measures of external load bias slightly toward mechanical properties and their monitoring can help manage the strain on the machinery of the body, which is important for structural tissue integrity. Internal loads bias toward physiological/metabolic stress, more accurately monitoring energy conversion machinery in muscle and the systemic response to training. Therefore, external load variables (e.g., power, speed) are best used in conjunction with internal load variables (e.g., heart rate, rating of perceived exertion, blood lactate) to obtain a more accurate picture of true physiological load.

Hormesis and Load

Simply stated, “hormesis is defined as an adaptive response of cells and organisms to a moderate (usually intermittent) stress.” As discussed, hormesis demonstrates the dose-dependency of the stress responses. In exercise, the ‘dose’ can be perceived as the ‘load’, which is the product of volume (i.e., how much training) and intensity (i.e., how hard is the training). As an oversimplified heuristic, I tend to think of the variables as an equation where:

Load = Volume × Intensity

Using this mental short-cut allows a quick visualization of how training parameters produce load stress. Keep in mind that this is very simplified. In actuality, I do not believe that intensity or volume are linear entities. Nor are they equally weighted. Scaling up intensity has a far greater effect in endurance activities on overall load compared to volume, as discussed previously. Not to mention the need to consider frequency as a parameter in the overall evaluation of the stress/recovery adaptation cycle. Perhaps we’ll touch on frequency later.

But for now, until next post….