Sunday, February 16, 12025 Human Era (HE)

In Theory

This post is a follow-up to a five-part series on energy metabolism and its relationship to stand up paddleboarding (SUP). The impetus for the metabolism series stemmed from a conversation with a client on energy systems. The conversation went into esoteric topics of energy exchange, and I realized that a refresher for myself was in order. I found that writing a few posts on anatomy and biomechanics specific to SUP served as a great review of my anatomical knowledge, and I thought it would be a fun exercise to refresh on some energy metabolism physiology.

The first five instalments covered an array of topics ranging from background basics to trying to define what energy is to musings on enthalpy and free energy and carbon (C) as the building block of life to fun topics like the mystery of where fat goes when you lose weight and more serious topics, like the methods of metabolism and anaerobic versus aerobic pathways.

My goal with these posts was altruistically selfish. The research required to create these posts would broaden my understanding of endurance training philosophy and physiology, and perhaps do the same for any interested readers. My intent was a series of posts to bridge the gap between theory and practice and provide a practical framework about how to operationalize and, if desired, improve the bioenergetics of someone’s SUPing. However, I seem to have gotten carried away, and the post(s) has(ve) morphed into a sweeping account about training theory and philosophy. Read on if you dare.

Methods of Metabolism: Recap

From the theory within the methods of metabolism post, we saw that despite the often-cited distinction between aerobic and anaerobic metabolism, in humans, all metabolism is ultimately aerobic. The amount and rate at which free energy is required determines the predominant metabolic pathway, but the classic distinction between aerobic and anaerobic glycolysis is more academic than practical. Broadly speaking, there are three major energy pathways or systems that are categorized, but they all end up in the mitochondria at the electron transport chain.

Historically, the three pathways/systems were divided into two ‘anaerobic‘ branches, the alactic and lactic systems, and the ‘aerobic’ system. I prefer to use the terminology of phosphagen, glycolytic, and oxidative (or mitochondrial respiration), as they are more descriptive of the processes involved and our current understanding of the physiology.

Traditional linear and modern manifold models of metabolism.

Sources: https://www.thesustainabletrainingmethod.com/

https://canada.humankinetics.com/blogs/excerpt/energy-systems

Keep this three system distinction in the back of your mind as we discuss more topics. It provides a useful framework for thinking about the underlying physiology governing endurance adaptations. But also keep in mind that physiology is spectral and the division of distinct metabolic categories is a construct rather than a reality.

Video Review

If you are one to prefer to video recap, this is one of the better ones that I have come across.

All Systems Go

As previously discussed, all these systems are active at all times but to differing degrees depending on the metabolic demand/duration of the activity and the starting state [i.e., nutritional status (e.g., glycogen stores), fitness, etc.]. Via the body’s various shuttle systems (e.g., phosphocreatine, lactate), substrates can be moved intra and inter-cellularly to where they are most needed/useful. Ultimately, your body needs adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to power its cellular processes and what it makes that ATP from mainly matters in the magnitude and molecular movement speed of metabolism (i.e., energy demand dictates the main metabolic pathway utilized). An intriguing analogy is to see the metabolic pathways as cogs on a bicycle drive train. They all turn simultaneously, but at different speeds, and are ultimately governed by the pedal cranks and front cog, which represents mitochondrial respiration. The chain cannot turn unless the front cog is in motion, and ultimately, mitochondrial respiration is dependent on oxygen availability for the final transfer of electrons.

What’s Up for SUP

Evidence suggests that people most commonly engage in SUP for fun and fitness. A sub-demographic of SUPers participate in SUP for competitive endeavours (i.e., racing, surfing). Both demographics benefit from a degree of aerobic fitness, but the latter group also requires a degree of anaerobic fitness for intense short bursts of activity during competition. Thus, it follows that endurance-based energy systems should be the bulk of focus for SUP competition.

Enduring Endurance

Endurance sports are characterised by repeated isotonic contractions of large skeletal muscle groups. Stand up paddleboarding for sure falls within that definition. Traditionally, aerobic training activities have been aimed at achieving this goal. Recently, the role of higher-intensity fitness training in endurance adaptations has gained more prominence.

Race Related

Given the nature of SUP racing, athletes would also appear to benefit from higher-intensity training directed at glycolytic and phosphagen energy systems for sprint and burst speed effort improvements. These efforts are necessary for position and placing, especially for starting and finishing an event.

Furthermore, the historic distinction between aerobic and anaerobic systems may be more theoretical than practical. It has been demonstrated that forms of training like high-intensity interval training (HIIT) benefit all energy systems, rather than just the high-energy flux (i.e., anaerobic or phosphagen/glycolytic) pathways. A question arises as to which methodological training approach is best suited for endurance generally or SUP specifically?

Confined by Camps

This may be an unfair characterisation, but it seems like there are two main endurance exercise training camps (though to be fair, this is not an all-or-none dichotomy, but rather a continuum of where the bulk volume of training intensity resides). At one end, it is the more traditional long slow-distance (LSD) approach, and at the other is the more recently resurgent, HIIT. I say resurgent since interval training has a long history. Modern documentation traces HIIT to the early 11900s HE, and interval training techniques date to well before then, too. The recent resurgence in interval investigation has revealed that HIIT can confer similar benefits to traditional LSD training, which has bolstered its popularity in our time crunched era.

Camps into Context

It is worth noting that as early as the 11964 HE Summer Olympics in Tokyo, we had a full spectrum of training styles on display as highlighted by the reference link from this Outside article, “How the “Norwegian Method” Is Changing Endurance Training.” The take-home message appears to be that many methods can lead to success. Though the caveat that the short intervals employed by Bob Schul might not represent the current manifestation of HIIT is worth pointing out (although 100 metre repeats seem to fall within the HIIT window in my world view).

For an excellent review of the last 100 years of endurance/distance runners’ training trends, see the section title, “Historical Trends in Distance Runners’ Training Principles,” in this article. The summary is that many of the methods we see as new and innovative today have been tried before and are now just modern makeovers.

In the context of the average ‘athlete,’ (cough, read ‘recreational weekend warrior’) the appeal of HIIT are the purported benefits that are similar to more traditional volume (i.e., think big time commitment) based protocols that can be achieved in less time. Though it is worth distinguishing the various protocols since some HIIT recipes require long recoveries and thus ultimately take more time than continuous training.

Elite Exceptions

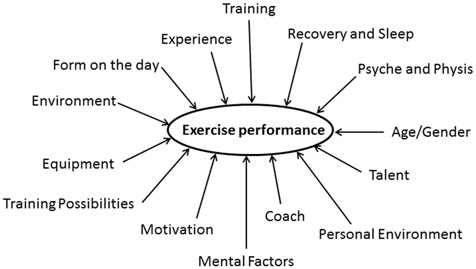

Responses to training are dependent on the physiological stress they induce and the body’s capacity to respond/recover from the stress. The resultant adaptation is dependent on the level of training of the athlete in relation to the stress applied, amongst several other factors known to influence exercise performance (see image below for examples). For those at the elite levels, there appear to be minimal shortcuts regarding the investment in overall training volume. At the same time, the evidence and practical insight suggests that some proportion of high-intensity training is a requirement to drive adaptation at that level. What is more open to debate is what proportion of training should be high-intensity versus low-intensity (i.e., training intensity distribution). The distinction of distribution has driven division within the distinct camps of endurance training.

Source: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283293450_Elite-adapted_wheelchair_sports_performance_A_systematic_review

Dweebie Dust-up on Distribution

Recently, the dogma on training intensity distribution has been questioned. Generally, three distinct models of distribution on discussed, pyramidal, polarized, and threshold. With a common consensus converging on polarized as the prized protocol. However, this contention is not without controversy. For an academic argument advocating if there are advantages of polarized versus pyramidal training, check out these two papers, “Polarized Training Is Optimal for Endurance Athletes” and “Polarized Training Is Not Optimal for Endurance Athletes.” As well as their respective responses, “Polarized Training Is Optimal for Endurance Athletes: Response to Burnley, Bearden, and Jones” and “Polarized Training Is Not Optimal for Endurance Athletes: Response to Foster and Colleagues.” For a slightly less pedantic perspective, check out the videos below, which feature a co-author from each camp. Or, check out this popular science piece by Alex Hutchinson summarizing the scientific stories.

One thing to note in the conversation is that the distributions of training intensity are using a three-zone model. Thus Zone 2 in this model is very different from the Zone 2 of internet hype (i.e., think of the five zone model that is common on many wearable fitness devices). Definitions matter, and it is important to compare apples to apples. For a great explainer on zone theory training check out this aptly titled video by the Global Cycling Network, “Training Zones Explained.” Zone 2, from the greater than three-zone models (of internet hype/lore) comes up later, so it is important to not get confused.

Considering where there is agreement between the camps, it seems that at the elite level, common practice is that a high proportion of training is done at lower intensity. Where there is disagreement is exactly how much is done at this lower-intensity. More specifically, what is the distribution between the moderate and high-levels of intensity in relation to the volume of lower-intensity work. Some of the controversy stems from what constitutes the training load intensity. Should this value be weighted toward the “session goal” as is suggested by the pro-polarized camp. Or is it more accurate to describe the training load by the actual time spent at a given intensity as is advocated by the pro-pyramidal camp. Correlated to this controversy is that many coaches and athletes may have a “session goal” intensity that is not actually being met in practice.

On top of that is what your load parameter is. Pick speed and get one result. Choose heart rate, and you get the opposite model outcome from the same training. Turns out, it is complicated. But for a good state of current affairs, at least in the cycling world, check out the video below.

Joes Versus Pros

Sometimes lost in the research and discussion on endurance training, however, are the distinctions between elite performance, general performance, and general health. For most people, doing a little bit more than what they are doing presently is going to confer the greatest health benefit and arguably even the greatest performance benefit. As an athlete transitions to the higher volume side of the activity spectrum, the details begin to matter more. Though, I would still argue less than most of us care to think, at least until the uppermost echelons of elitism. For the average athlete, whether you are engaging in LSD or HIIT (or some hybrid in between) has less to do with optimization and more to do with interest/engagement and time availability. For those who prefer LSD and have the time, that system of training will work. For those who do not have the time or interest, there is HIIT as an alternative. Both will give you improvements in health and performance. And for everyone else, there is a spectrum of styles in between to whet your palate.

Professional Proportions: Theoretical Pontification and Practice

Keep in mind that at the most elite levels, the total amount of HIIT that comprises a predominantly LSD-based training system following the sangraal traditional 80/20 split (i.e., polarized model) is much more than the mean of most peoples general exercise volume. Twenty percent of eight hours of training (which would be low at the elite level) is still over an hour and a half of HIIT. This mostly holds true for any of the tripartite training intensity distributions (pyramidal, polarized, or threshold), with the exception of the lowest volumes using either pyramidal or threshold approaches where the proportion of the highest intensity level of exercise would be lowest. We will get into the why of why this may matter later. But it is worth noting, that at less than elite training volumes, many people can handle programs that focus more on HIIT with a reduced risk of overreaching/training while achieving adequate fitness improvements in less total time (more on this to come too). And it goes without saying that it is most likely the case that in practice no one, even at the elite level, is truly following an 80/20 split.

Does Distribution Matter: Horse versus Cart

Highlighted in this video with Mark Burnley on training zones is the notion that training intensity distribution is an outcome, not a goal. Unfortunately, in Burnley’s view, some coaches, athletes, and physiologist have started to look at training intensity distribution as the goal and not the outcome to the detriment of training. In his opinion, it is a classic case of putting the cart before the horse. The take-home message is that training intensity distribution should be diverse, but the diversity should be driven to meet the demand.

It may be that newer more internally calibrated training approaches to scale intensity for optimal health and performance may confer better benefits to those who have the means. Though, I suspect recreational (and elite) athletes will still need to be mindful of their training load (more on this later) concerning cumulative stressors of life regardless.

Stay tuned for the next instalment next week…

5 thoughts on “Theory’S UP: SUP Energy Practice. 1”