Sunday, March 2, 12025 Human Era (HE)

- Preamble Ramble

- The Elusive Threshold Rears Its Head Again

- Dosis sola facit venenum (the dose makes the poison)

- Toilet Tissue. Is That the Issue?

Preamble Ramble

This post is a follow-up to a five-part series on energy metabolism and its relationship to stand up paddleboarding (SUP) and the third instalment to this series. Click here for the first instalment, which is a recap on metabolism and an overview of the philosophical and physiological underpinnings of endurance training. Click here for the second instalment on catecholamines and the exercise stress response.

The Elusive Threshold Rears Its Head Again

While the longstanding idea of an anaerobic threshold has been questioned recently since the distinction between aerobic and anaerobic glycolysis has been proven arbitrary, the idea of a threshold for scaling exercise intensity continues to provide appeal for the communication and prescription of exercise intensities. To be sure, there is a spectrum of metabolic processes that occur as exercise intensity increases. Somewhere along that continuum, it can be useful to consider a point where exercise capacity goes from indefinite to finite (though I would caveat that this point is not absolute, but rather relative to the event and conditions, i.e., multiple thresholds exist depending on differences in activity duration and intensity). These theoretical points are the elusive “threshold” and differ depending on the exact definition used. One version of the threshold is the so-called lactate threshold, the point at which there is an accumulation of lactate within the blood. Practically speaking, there seems to be an association between various levels of lactate accumulation and activity tolerance/endurance. For an excellent popular science account on the determinants/limits of human endurance across a spectrum of activities, check out Alex Hutchinson’s Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance.

Accumulation: Balancing Production and Clearance

The measurement of blood lactate as a surrogate of a metabolic transition point (i.e., threshold) continues to have an appeal within sports science circles. However, it should be noted that the measurement of lactate within the blood represents the balance between cells producing lactate (aka. drivers) and cells consuming lactate (aka. recipients). Furthermore, how/where the sample is taken has implications, with the most evident being that blood lactate is a sum measure represented as a concentration. The balance between production and consumption is part of a wider conceptual framework known as the lactate shuttle theory, which demonstrates that lactate produced glycolytically can be moved about the body and utilized oxidatively as a preferential carbon fuel source.

Measuring the activity of specific metabolic pathways during exercise still remains elusive. Thus, blood lactate measurements are used as a not perfect but practical estimate. Elevated blood lactate levels represent an imbalance between lactate production and consumption during metabolic stress and are reflective of high rates of energy turnover and glycolytic flux within cells. Various ways of determining the elevation of blood lactate are known collectively as the lactate threshold, with specifics related to the exact values or protocols employed. The utility of a lactate threshold is that it correlates well with physical performance.

Dosis sola facit venenum (the dose makes the poison)

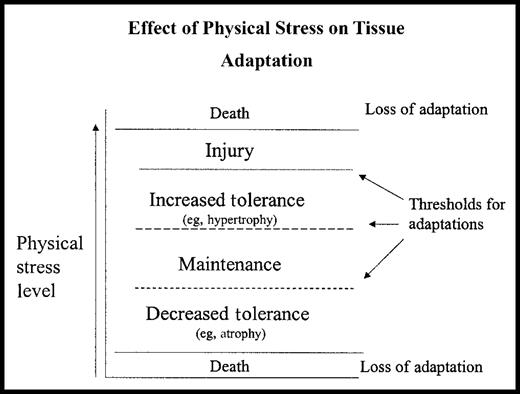

As mentioned earlier, the benefits of exercise are dose-dependent. The response to the stress of exercise is hormetic. Not enough exercise or physical exertion is harmful to your health, but at the same time, so too is too much exertion. To draw on the famed 119th-century (HE) famed fairy tale, it is a Goldilocks phenomenon, not too much or too little. There is an ideal zone, the hormetic zone, where the adaptation to the exercise stress imposed is favourable. With the correct application of exercise stress and recovery (emphasis on recovery), the therapeutic zone of exercise can be increased via the phenomenon of supercompensation. That increase is depicted in the image below as a broader adaptive zone with a larger bandwidth for “increased tolerance” and “maintenance.”

Source: https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article/82/4/383/2837004

Increasing Intensity: Lactate Threshold and Catecholamines

As training intensity increases, so too does the body’s catecholamine response. Evidence suggests that a marked elevation in circulating catecholamines occurs when exercise intensity results in an accumulation of blood lactate (i.e., intensities above the lactate threshold). Therefore, exercise becomes more risky for immune system compromise when the intensity surpasses the lactate threshold, and this should be considered with exercise planning and prescription (again chalk one up to the refined version of the ‘Norwegian Method’ with tight monitoring of blood lactate levels). Another risk factor is duration, as catecholamines will tend to rise with prolonged duration activity even if the intensity is low. This effect can be mitigated with proper nutrition to avoid depleted glycogen levels. Catecholamine release during exercise is a response to metabolic strain, and many of their actions are aimed at the mobilization of fuel stores and liberation of energy acutely. If the body senses that energy stores are compromised, there tends to be a greater catecholamine response to offset the discrepancy.

On-Demand: The Brain Calls the Shots

As discussed in this video, ” Are You Overtraining?,” from the Global Cycling Network with Iñigo San Millán, some of the potentially detrimental effects of catecholamines on performance (and health) can be offset if the brain does not perceive a threat of hypoglycemia. Spoiler alert! Another point is chalked up for carbohydrate consumption (or in a pseudo mind over matter trick, at least a swish of sugars in the mouth, to gain a similar effect)! Basically, your brain needs (or at least needs to think it has) a steady supply of glucose to function. But, if the brain perceives a threat to its sugar supply, it will do anything and everything to curtail the shortage. In the context of exercise, that means stopping your muscles from burning up their (or the brain’s backup) glycogen or sugar stores. When you “bonk” or “hit the wall” during exercise, the brain shuts down the body to save itself (more on this later when we discuss fatigue).

Tissue Types and Training

Other aspects of endurance training that need to be considered beyond metabolism are mechanobiology or biomechanics. While the metabolics of endurance are mostly concerned with two of the four basic animal tissue types, i.e., cardiovascular (epithelial and muscle tissue) and musculoskeletal [muscle tissue (and yes I realize that “musculoskeletal” includes another class – connective tissue – but like many things our tissue classes don’t quite fit our human curated classification boxes)] systems, biomechanics gives greater consideration to other the other two main tissue types, i.e., connective (in this case tendons and bone) and nervous tissue (and yes, blood is a connective tissue by definition, so the former distinction between cardiovascular and musculoskeletal pretty much goes out the window).

Kleenex Interlude

Tissues are “an aggregate of similar cells and cell products forming a definite kind of structural material with a specific function, in a multicellular organism.” The parallel in nomenclature stems from the etymology of tissue in descibing woven-like structures, as is the case from the brand Kleenex or generic term facial tissue. Tissue arose from the Middle English tissew, a variant of tissu, the Middle French/Old French, noun use of past participle of tistre, meaning ‘to weave,’ from Latin texere.

Back to Types and Training

As depicted in the image below, in addition to the more classic physiological variables, the physical characteristics (i.e., anatomy and biomechanics) of the body also affect performance. It is not just function. Form plays a role, too.

How Tissue Types Talk: Mechanotransduction

I recall being re-introduced to the concept of mechanotransduction in physical therapy school by way of mechanotherapy. Though my initial introduction, unbeknownst to me at the time, to mechanotransduction was during my undergraduate degree. We covered the quintessential case of mechanotransduction, Wolff’s Law and bone growth. Wolff’s Law states that bones will adapt to the degree of mechanical loading they endure. However, at the time during my undergraduate studies I failed to frame the concept of mechanotransduction more broadly and realize that mechanical force or load is ultimately at play for all signalling processes in the body. It took until my re-exposure in physiotherapy school for the concepts to click. In hindsight, it is now clear that even chemical signalling is fundamentally a physical (i.e., mechanical) process when considered at the molecular level.

Multiple Nuclei

Thus, when it came to thinking about training load in the context of endurance conditioning, the mechanical stress/adaptation relationship immediately came to mind. This understanding was coupled with a recent re-emphasis regarding the fact that muscle cells are multinucleated from the Huberman Lab guest series with Andy Galpin (click here for the time-stamped clip link). Specifically, Dr. Galpin highlighted how this factoid factors into why muscle is such an adaptable tissue. The uniqueness of myofibrillar multinucleation in contrast to other cell lines that are typically mononucleated (though exceptions exist like osteoclasts, hepatocytes and neurons which are known to be multinucleated in normality) means that muscles are more adaptable as a result of the multiple regulation centres located throughout the various regions of the cell.

A likely evolutionary pressure that drove myocytes to be multinucleated is their size. Myocytes are large and exceptionally long. In order to communicate efficiently from one end to the other, they required multiple regulation centres. As a analogy imaging an office or city that is super long, it would be easier to coordinate and make decisions faster from the west end to the east end if there was more than one boss/manager or city hall across to overly long distance. Hence, the need for multinuceation.

Booming Blood Flow

In addition to multinucleation, tissue adaptability is also heavily influenced by blood flow and metabolic activity/flexibility, not to mention gene expression and neural plasticity. Here again, muscle cells excel. With respect to blood flow, muscle blood flow at rest is 1-4 millilitres per minute per 100 grams. This rate can increase to 50-100 millilitres per minute per 100 grams at maximal exercise, a 20 to 50-fold increase. As a comparison, tendon blood flow during exercise is estimated to increase by about seven-fold.

Mega Metabolism

Similarly, metabolism in resting muscle cells is relatively low compared to more metabolically active tissues like the liver, brain, heart, and kidneys. But myocytes can increase their metabolism more than 50-fold during maximum exercise. In fact, muscle ATP production can increase up to 1000-fold during maximal exercise! This power production is echoed by the number of power plants, i.e., mitochondria. Tissues that have high energy needs have high numbers/concentrations of mitochondria. Muscle and nerves cells are among some of the most energy hungry cells with thousands of mitochondria per cell.

Gene Generation and Networked with Neurons

Two other factors that contribute to muscle tissue adaptability are gene expression and neural connections. Both tie into regulatory mechanisms, with the former related to multinucleation. Muscle has the capacity to change its mass and phenotype in response to physical activity. Nerves cannot go without mention in this process as they ultimately govern the activity of most muscle cells.

Toilet Tissue. Is That the Issue?

All this is to say that many of the other key tissues involved in endurance training adaptations are less malleable. That is not to say that these tissues are doo-doo or poo-poo the changes these tissues are capable of. They are still highly adaptable. But, it is worth considering that they change slower than muscle tissue, and they are often the bottleneck in tissue adaptation, particularly at the macro-architectural/mechanical level. All tissues will respond to physical stress, but rather, it is “A question of time: tissue adaptation to mechanical forces,” as per the aforementioned apt article appellation.

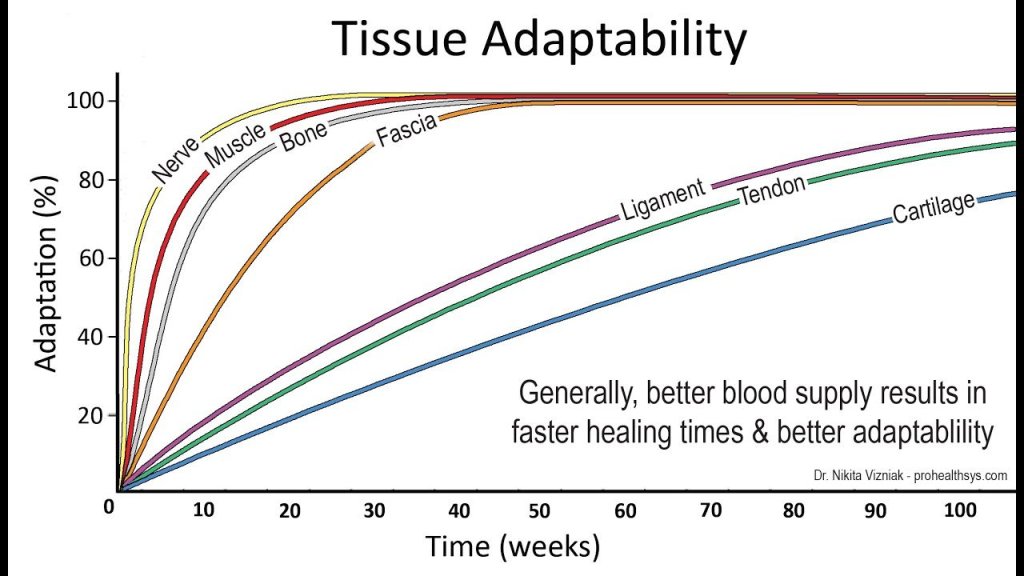

While perhaps not perfectly precise, the pictograph below presents the principle premise. Depicted are the adaptation rates of various tissue types. Of note is that the less perfused tissues (i.e., ligament, tendon, and cartilage) are located to the right of the graph and adapt more slowly than the more perfused tissues on the left (i.e., nerve, muscle, bone, and fascia). It is hard to find a definitive answer, but estimates range from four to nine-fold increases for the time to adapt when comparing more active tissues like muscles and nerves to more inert tissues like tendon and cartilage.

The rates of tissue adaptation are another reason why LSD training is the tried and true method of endurance athletes. In addition to driving favourable metabolic changes, the lower-intensity means lower mechanical stress. This is more manageable for all of the tissues involved, but particularly the tendons, which are the muscles’ connection to the bone, and therefore endure similar mechanical strain, but without the same responses range or rate.

The higher volume of training associated with LSD can still pose a threat for repetitive strain injuries. The body’s training load capacity can be surpassed by too much intensity, volume, or some combination. While the slower speeds (i.e., lower forces) associated with LSD training are not fail-safe against overtraining, they seem to offset the risk to a considerable degree.

… until next time…

3 thoughts on “Theory’S UP: SUP Energy Practice. 3”