Sunday, February 23, 12025 Human Era (HE)

Preamble Ramble

This post is a follow-up to a five-part series on energy metabolism and its relationship to stand up paddleboarding (SUP) and the second instalment to this series. Check out the first instalment here.

Theory and Practice

While science presently does not have the full answer as to the recipe for optimal endurance development, at present, practical and scientific evidence suggests lower intensity/higher volume is the key to success (especially at elevated levels of eliteness). The deviled details are exactly what the splits and intensities are. Traditionally, a high frequency and volume of lower-intensity training is believed to be beneficial to peripheral physiological adaptations favourable to endurance (e.g., increased mitochondrial biogenesis and capillary density). In contrast, higher-intensity training is believed to stimulate central adaptations (e.g., increased stroke volume). However, more recent work points towards high-intensity training driving peripheral adaptations in fast-twitch motor units. The growing consensus appears to be that you need both stimuli since they seem to drive independent but mutually beneficial adaptations to performance.

To summarize, the most recent evidence suggests that exercise at higher intensities [e.g., sprint interval training (SIT) and/or HIIT] promotes enhanced mitochondrial respiration and function (think of this as improved efficiency). Conversely, prolonged low-intensity and high-volume (i.e., traditionally LSD training) endurance exercise leads to increased mitochondrial content (or density) within the muscle (see image below).

Source: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5983157/

Brief Notes on Adaptability (well, sort of brief…)

My foray into the science of endurance training has me wondering why the lower-intensity recipe seems to be key. Perhaps it is my bias from my own athletics/training background that training needs to be intense. I have fond memories of sprint-style conditioning drills consisting of “17s” and “Suicides,” geared toward improving speed, endurance (in the multidirectional sports sense), and grit. These drills are maximum to near-maximum sprint efforts of short duration. So, they are high-intensity (sprint intensity in the technical sense) but low-volume.

Upon reflection, that is likely where the nuance lies. My past experiences of hard, or intense, training have always been lower volume, despite me truly realizing it. At the same time, most of my multidirectional sports experience (i.e., basketball) involved the majority of exertion at a lower intensity, whether in training or competition. From the limited sample of slamdunk-supporting sportspeople I surveyed, it would seem I am not alone in overestimating the training stimulus (i.e., overreading the intensity and underreading the volume). Ballers believe and hoopers hope that the toughness of their training is more intense than the truth. While training for and competing in basketball (and other multidirectional sports for that matter) involves high-intensity intervals, the majority of activity time (i.e., greater than 50%) is at a low intensity. I can only surmise that the more reactive and dynamic aspects of multidirectional sports distract participants’ perceptions pertaining to this aspect of their training. Conversely, my guess is the continual, monotonous nature of endurance-specific sports put the lower intensity levels of exertion front and centre without the added aspect of constant reactions to opponents or chasing/controlling balls.

Maybe Intensity Isn’t All It’s Cracked Up to Be

To be sure, endurance training is intense in the general sense of the term. It would be foolish to say that it is not intense to accumulate the training volumes of elite endurance athletes. Even the strain sums of sub-elite sportspersons score as strong on the scale of strenuousness. But, according to the sports science definition of “Intensity,” the bulk of the training is low-intensity. That has always seemed odd to me. Nor does it seem that am I alone in noting this peculiarity, given the abundance of endurance athletes who overtrain. Could the efforts seem so soft that athletes believe they must strain harder to gain effect? Or maybe endurance athletes have a high level of neuroticism that results in stupendous training volumes despite their intensity being in check?

Whatever the case, it still begs the question, why is it that low-intensity seems best suited for endurance training gains?

Why Less is More: Training Thoughts

In my research, I came across this article, “What is Lacate and Lactate Threshold,” by an expert in the field, Iñigo San Millán. Taken in context with the current hype around the Norwegian Method, the article gave me a minor epiphany. San Millán highlights how fast-twitch muscle fibres have an abundance of one type of monocarboxylate transporter, i.e., MCT-4, that mainly functions to move lactate out of the cell and away from these fibres. Whereas slow-twitch muscle fibres have a greater abundance of MCT-1, which brings lactate inside these fibres (or cells). Low-intensity training has been shown to increase the number of mitochondria (increasing MCT-1 and mitochondrial lactate dehydrogenase), thereby increasing lactate clearance capacity. Training at higher intensities increases glycolytic flux and improves the capacity to produce lactate as a by-product of the drive towards faster ATP production for greater work output.

The article gave me insight into the beauty of the Norwegian Method. My epiphany was that lower intensity volume provides the stimulus for improved lactate clearance, while at the same time, the lactate-guided higher intensity intervals allow athletes to improve their glycolytic capacity in fast-twitch fibres. By limiting the accumulation of lactate, the training stimulus does not result in the potentially detrimental effects that high-intensity (over)training can have on the pyscho-neuro-endo-immunological systems (more on this below).

It seems less profound of an insight writing it now. But my current belief as to why the Norwegian Method has been so successful is that it strikes a balance between optimizing intensity and volume and thus achieving an optimal training load. This is done by minimizing the range between over- and under-training by fine-tuning the internal training load of psychophysiological variables by including blood lactate as an internal training load measure in addition to the more variable measure of heart rate (again more on this to come).

Caveat: The Catch with Catecholamines

My deep dive into endurance training and the why behind low-intensity/high-volume training brought me to what I see as the catecholamine conundrum. Catecholamines are a class of compounds that act as both neurotransmitters and hormones (for a good summary listen on hormones check out this episode of the BBC‘s In Our Time titled, “Hormones“) in the body. Catecholamines are integral in the body’s stress response, specifically the sympathetic nervous systems‘ [i.e., fight, flight, and don’t forget freeze (as is highlighted by this episode, “Frozen in a Burning 747 (Tenerife Air Disaster 2)“, of Cautionary Tales)] side of the action, which is set in motion during exercise [or other physiological (or psychological) stressors]. Interestingly there is a burgeoning field of research that has coined the term “exerkines,” to define a class of signalling moieties that are released in response to exercise that have endocrine, autocrine, and paracrine effects. Catecholamines definitely fall within this newly labelled class of exerkines. The body’s catecholamines are dopamine, epinephrine (aka adrenaline), and norepinephrine (aka noradrenaline).

Catecholamines and Exercise: You’re Stressing Me Out

As a physiological stressor, exercise is known to activate the sympathetic nervous system in a dose-dependent manner. This seems to happen as a response to a disruption in cellular homeostasis consequent to metabolic strain that results in the production of reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen species. In an attempt to restore homeostasis, catecholamine release is part of the body’s rapid first line of defence.

For a very thorough account of the acute versus chronic stress response, check out this video below from But Why? Keep in mind that stress is a necessary stimulus and is not necessarily bad.

SAM HPA: Good Versus Bad Stress

As a brief summary, the stress response has two arms of action, but they overlap. The faster, short-term response comes from the Sympathetic-Adreno-Medullar (SAM) axis, and the slower, longer-term response arises from the Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis. The sympathetic-adreno-medullar axis is set in motion by complex actions in the brain’s hypothalamus region when a stressor is percieved resulting in signals to the adrenal medulla to release the catecholamines norepinephrine and epinephrine into the bloodstream. Norepinephrine and epinephrine have the following effects on the body: maintaining alertness, metabolic actions (increased glucose via glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, lipolysis, increased oxygen consumption and thermogenesis) and cardiovascular actions. These actions collectively prepare the body for fight or flight. The sympathic-adreno-medullar response is very rapid as it is set in motion by sympathetic nerve fibres that travel to the adrenal medulla.

At the same time, the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis is also set in motion by way of the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus synthesizes and secretes the hormone/neurotransmitters corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which travels to the anterior pituitary gland. Here, corticotropin-releasing hormone stimulates the synthesize and release the adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which in turn is secreted through the hypophyseal portal system and travels to the adrenal gland, acting on the cortex and stimulating glucocorticoid synthesis and secretion. In the human body, the main glucocorticoid is the infamous stress hormone cortisol. A key feature of cortisol is that it is a fat-soluble hormone, so it can freely diffuse across cell membranes and enter cells where it can exert epigenetic effects.

In the popular press, cortisol often gets a bad rap. However, this is slightly misguided. Cortisol is essential to human health. The key factor is that stress is time, duration, and dose dependent. While acute stress serves a role in adaptation, optimal health, and survival, chronic stress is associated with maladaption and negative health outcomes by way of prolonged effects of exposure to cortisol. The biological stress response seems to have evolved to mainly deal with short – to mid-term disruptions.

As per the schematic below, environmental stressors disrupt the body’s homeostasis. The sympathetic nervous system is called on to respond, resulting in a release of catecholamines, which ultimately function to mobilize the body’s energy stores via changes to the metabolic, respiratory, and cardiovascular systems. At the same time, the immune system is engaged to mount a sterile (i.e., non-pathogen mediated) response to minimize and offset any damage from the metabolic (and mechanical, in the case of physical exertion) strain and help return the system to homeostasis.

Source: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10715762.2020.1726343

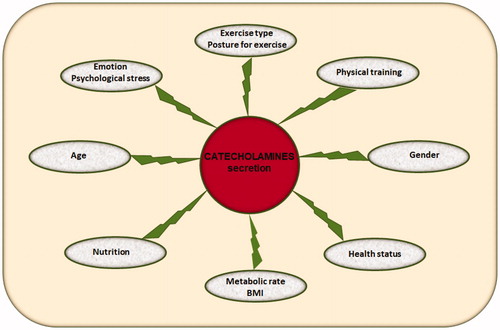

Specific to exercise as a stress, the intensity and/or duration are the main determinate(s) as to whether the effects are beneficial or harmful. High-intensity exercise, in particular, has the potential to induce significant stress on the body. If the stress load is above the body’s current capacities, the signalling powers of catecholamines and their interaction with the immune system and metabolism can be detrimental (not to mention the interaction of cortisol with immune function as per the But Why? video above). The body’s catecholamine response to exercise is mainly modulated by exercise intensity and duration, but other factors are at play, too, such as exercise type and posture, training status, sex, health status, body mass index (BMI), nutritional status (e.g., glycogen stores), age, and emotional/psychological stress, as per the icon below. Note that these factors are highly individual in nature, and so too, is the body’s catecholamine response to stress (or exercise).

It is worth noting that the duration of exercise, independent of intensity, also results in elevated catecholamine levels. It is possible that high volumes of training, even if the intensity is appropriate, can be detrimental. How much is too much, and when the benefits of exercise change to harms remains unclear. For an in-depth account of the topic, check out this review article by Kruk et al., “Physical exercise and catecholamines response: benefits and health risk: possible mechanisms.”

As a brief summary of the paper, generally speaking, the acute changes in catecholamine concentrations during exercise are beneficial. Athletes and those who are physically active have been shown to exhibit a greater catecholamine response to exercise or physical activity. The same can be said for the glucocorticoid response to exercise, especially since it is there long lasting epigenetic effects that can have greater influence. The majority of people are familiar with the touted benefits of moderate to vigorous exercise, and those effects remain irrefutable. However, in contrast, extreme levels of physical exertion, whether high-intensity or ‘endurance’ exercise, particularly when it is not preceded by proper training, can be a strong mediator of immunosuppression and cellular macromolecular damage due to increased generation of free radicals, reactive oxygen species, and reactive nitrogen species. While the exact intensity and duration at which exercise changes from beneficial to harmful remain unknown and are individual in nature, it is safe to say that in the vast majority of circumstances, exercise is beneficial and healthy.

Stay tuned for the third instalment next week…

3 thoughts on “Theory’S UP: SUP Energy Practice. 2”